…

…

…

…

Bought this when I was a teenager, and it traveled with me during my hippie years. I would often upset the mood when everyone was stoned and or tripping by putting Ella on—it was like parent music at the time I suppose—but my taste often upset others—I’d put on Patsy Cline or Yoko Ono too—very different ladies, but receiving the same protest when everyone was tripping. My sublime heavens were other people’s bummers I learned early on.

…

…

…

…

…

…

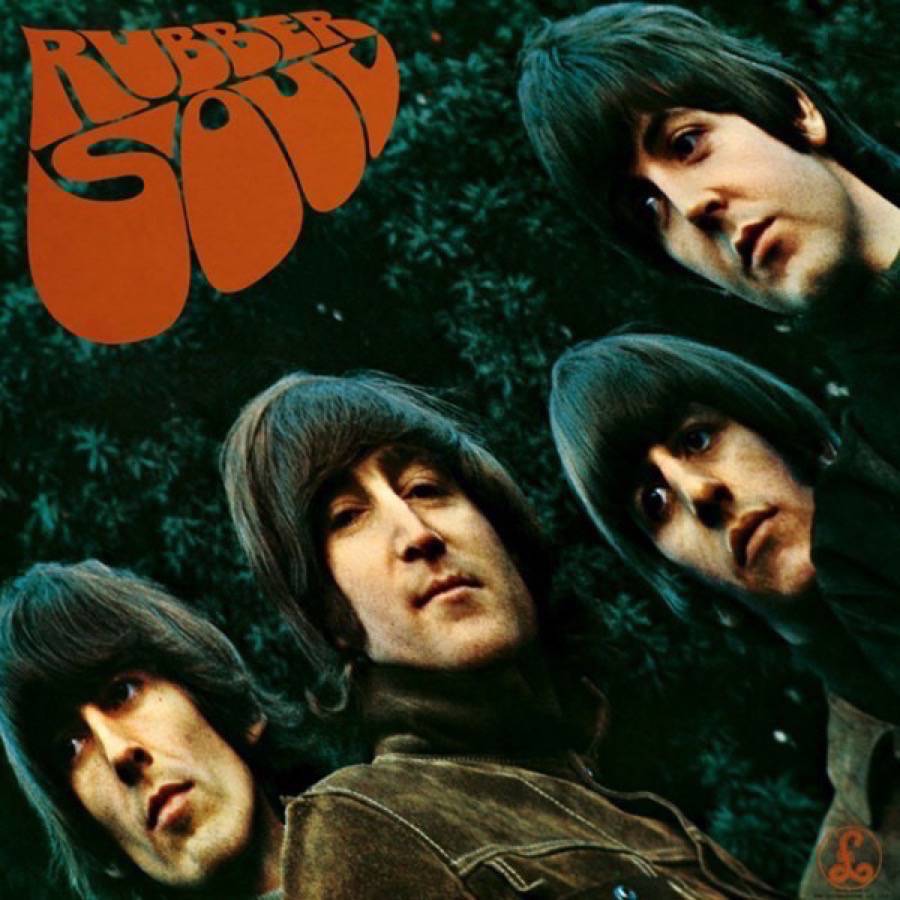

I am thinking that Rubber Soul may have been a Christmas present from Aunt Louise in 1965 or maybe I bought it. It is my favorite Beatles album and I have probably listened to it more than all of the other albums put together, but I could be wrong about that. Some say that if all that was left of the Gospels was The Sermon on the Mount, it would be enough. If all I had was Michelle, Norwegian Wood, Drive My Car, The Word, Nowhere Man, I’m Looking Through You, and In My Life (which John Lennon claims was his first major work), it might be enough. It’s the perfect day (it’s always the perfect day) to listen to Rubber Soul.

…

…

…

…

…

…

It was probably around 1971 when a lover at the time—we’re still friends—gave me this Nina Simone album. Even if I had not been in love I would have loved it even if I’d found it on the sidewalk and carried it home. I only saw Nina Simone perform once; it was in a sort of jazz revue at the Spectrum in Philadelphia—1972?—I remember Pharoah Sanders was there, and Billy Paul, who was riding high with the Philly Sound with Me and Mrs. Jones. He was great, and may have been, a hometown boy, the favorite of the evening. But Nina Simone, wow. She came out barefoot in a slinky shimmering emerald gown that pretty much revealed her pear-like breasts; there was a golden anklet if I remember, and her band was very African and minimal, a kora instead of a guitar, stuff like that. It may have been—but for the Cramps who gave an entirely different performance though also in Philadelphia—the greatest performance I’ve ever seen. When she played the piano, you could have heard a pin drop, not just out of awe, but an awesome fear as well that if you did make a sound, her presence was so powerful, that she could reach up into the stands, and slap you upside your head even if you were, like me, way up in the bleachers near the ceiling. I hardly breathed. Don’t Smoke In Bed, which she did not sing at that concert, but is on this album, is simply one of the greatest renditions of anything ever sung from the present to the beginning of time and back again.

…

…

…

…

…

…

The first real concert I ever saw—not counting Gary Lewis and the Playboys in Atlantic City in 1967—was Marlene Dietrich in 1968. I was going to Temple University at the time and took a bus to NYC with my friend Pat. It was the first time for either of us and we wandered around Time Square drinking in bars because it was legal at 18 back then. With a little bit of serendipity we wound up at a Saturday matinee starring Marlene Dietrich, and got tickets for the very last row up there next to the ceiling. I don’t remember if Burt Bacharach was conducting, but that concert and the album, which I bought a little later in 1970 maybe, are pretty much the same. One memory that sticks with me was that an old German couple sat next to us, and the husband kept crying and crying; sometimes he sobbed. I read somewhere years later that Dietrich rehearsed again and again. It was all planned. I believe she might have even planted people in the audience to call to her responses when she needed them. In her dressing room, Rex Reed reported, she scoured the bathroom with Comet. Of course, there were the stories about her squeezing into her girdles and gowns, pulling her skin back into the wig, getting rid of those wrinkles the best that she could; and getting into those heels, sometimes she’d bleed. Working with von Sternberg in the 1930’s, she became an expert on lighting, and knew the illusion, the effect that she wanted. And she often designed and sewed her on clothes. Falling in Love Again, I Wish You Love, her concert was as flawless as her album and to listen to the album is to remember the concert again. In my early twenties, I wrote to my friend Fred that I wanted to sing the Blues like Big Mama Thornton. “I’d think about Marlene Dietrich if I were you,” he wrote back. An aside, a little fact: when she died in Paris, they covered her coffin with the French flag; on the way to Berlin the American flag was added, and then in Berlin the German—obviously some people loved her.

…

…

…

…

…

…

I’ve kept Big Mama Thornton’s Stronger Than Dirt in a box under a bed somewhere, a record so scratched it’s unplayable even if I had a record player to play it on, but I just can’t throw it out. I heard of Big Mama Thornton long before I actually heard her. Janis Joplin made her famous singing Ball and Chain. Though I could never sing like Willie Mae Thornton—you’d have to be hooked up to the power that is the power from the beginning of time in such a way that I am not, but I understood by listening to her what it means to sing, the highs and lows, the bitter and the sweet; she had nuance and could reach it all. She sings both Hound Dog and Ball and Chain on Stronger Than Dirt and versions–I cannot call them covers–of other songs no one I’ve heard has ever matched. Lucky Old Sun! Funky Broadway! I Shall Be Released!

Because I really wrecked my Stronger Than Dirt by playing it a million times, I looked for tapes and CDs later on, but her label Mercury never released any. The bastards. What were they waiting for? All of her heirs to die? Mercury never was good to her; they hooked her up with the worst bands when she toured—once on stage in frustration she pushed away her lousy drummer and began to play the drums herself.

On PBS a while back, they did a show about female rock and blues singers and did not even mention her—I could not fucking believe it—Willie Mae Thornton was not just a branch on the Rock and Roll Tree of Life—she was damn near the trunk down near the roots where the Blues let her go to become what she was. She was her own worst enemy, of course—dressed like a man back in the 50’s when entertainers didn’t do that, and she drank herself to death shrinking into that skinny little frame she was at the end. But the woman was triumphant.

When I sing House of the Rising Sun, I sing the last line of the last stanza like Janis does in Ball and Chain:

I’ve one foot on the platform

one foot on the train

I’m going back to New Orleans

to wear that ball and chain

I really slowly let out that “ball and chain” the best that I can there at the end. Big Mama did it first; Ball and Chain was her song.

By the way, I’ve added my own stanza to House of the Rising Sun, before the last stanza:

I’ve cast my pearls before the swine

like opium been used

Day and night without respite

I’ve suffered every fool.

Janis and I just carried (carry) Big Mama on. One thing leads to another, out of the many one.

…

…

…

…

…

…

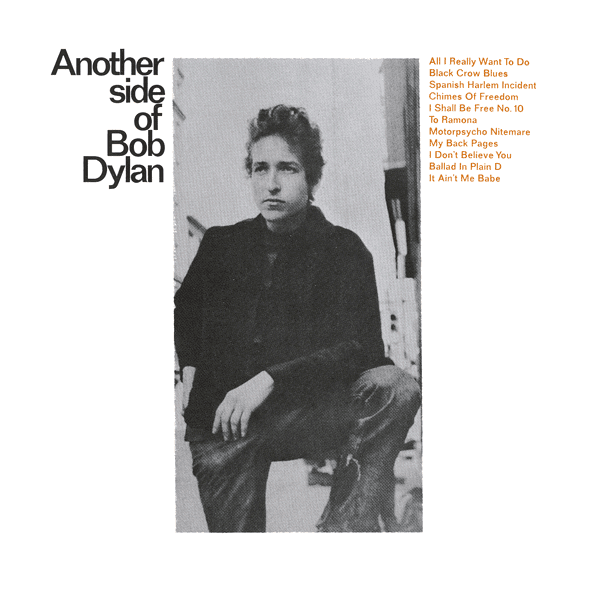

I turned 16 in August of 1965, and the songs that led up to it that summer were really something. There was Stop! In the Name of Love by the Supremes. My Girl by the Temptations. Ticket to Ride by the Beatles. Can’t Help Myself by the Four Tops. Tracks of My Tears by the Miracles. Nowhere to Run by Martha and the Vandellas. Help Me, Rhonda by the Beach Boys. We Gotta Get Out of This Place by the Animals. Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag by James Brown. Goldfinger by Shirley Bassey. I Can’t Get No Satisfaction by the Rolling Stones, which got kicked out of first place by I’m Henry the Eighth, I Am by Herman’s Hermits believe it or not. That July, I’m Henry the Eighth reigned. There was also What the World Needs Now by Jackie De Shannon, I Got You Babe by Sonny and Cher, For Your Love by the Yardbirds, All Day and All of the Night by the Kinks, and Mr Tambourine by the Byrds. I will have to stop somewhere, so I’ll stop here except to say that August around my birthday Like A Rollingstone by Bob Dylan was also released, and it, along with Mr. Tambourine Man, would change my life.

I’d been working on a novel that summer—I’d been working on it all year, about ancient Rome, full of gladiators, the mad Emperor Domitian, and a cast of other characters. My parents went on a vacation leaving me in charge of my brother Scott and my sisters Cathy and Peggy alone in the house way up there in the mountains with a garden full of sweet corn and tomatoes to pick and eat when we wanted. We played Monopoly all day and night, ate the crab cakes, french fries and fish sticks Mom left in the freezer, and I guess my siblings played while I worked on my book of circuses, orgies and adventure.

The radio was always on and the hits, as you can imagine, kept on coming. I liked a station in Buffalo and a station in Boston. On the station in Boston one night the DJ played Bob Dylan singing Mr. Tambourine Man. The song sung by the Byrds I heard everyday that summer, but when I heard the original, looking through the screen porch at the fireflies outside like so many blinking eyes illuminating the night, I thought Bob Dylan was an old black man singing—What did I know? I’d already memorized the Byrds’ version, and when I discovered there were more verses, I became so excited by how wonderful English could be—that English could sound beautiful had never occurred to me.

Then take me disappearing through the smoke rings

of my mind

Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves

The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach

Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky

with one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow

When my parents got back and I had access to a car, down the mountain I went and bought the first Bob Dylan album that I saw, Another Side of Bob Dylan. I didn’t know there was another side. I was familiar with Blowing in the Wind, of course—Who wasn’t?—but that, as far as I knew, was Peter, Paul and Mary. Another Side of Bob Dylan was recorded in one take, leaving in the the slurs and mistakes, just like the Beats, first thought the best. He might have been on amphetamines too, but back then, who wasn’t? I loved every song: I loved Bob Dylan. By the time Highway 61 Revisted came along, I was ready for it. Hearing beauty was seeing it too, and, without its fleeing, like some glimmering butterfly or snake, I wanted to reach out and touch it, create it and hold it. Somehow I had to have it. I knew that all I wanted was to be a poet. That flame, as I knew it, started then in me and the desire to keep it lit has yet to leave.

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

Once in my early twenties while listening to a blues song with my friends Don and Ruth, I was enchanted by the harmonica and said to them, “Isn’t that beautiful?” When Don mentioned the guitar and Ruth the piano, I understood that we all hear the same song differently.

I hear the harmonica and have enjoyed listening to some play it particularly Bob Dylan, Big Mama Thornton, and James Cotton, who gave one of the best concerts I’ve ever seen, up there with Nina Simone, the Cramps, David Bowie and Lou Reed. I’d gone to see John Mayall, but was blown away by the opening act—at one point—I am not making this up—James Cotton did a flip, a somersault and slid to the front of the stage on his knees blowing on his harmonica with all of his glorious might. I was very stoned at the time, and it seemed impossible—James Cotton was heavy even back then—but a friend I was with affirmed later on that I had not hallucinated.

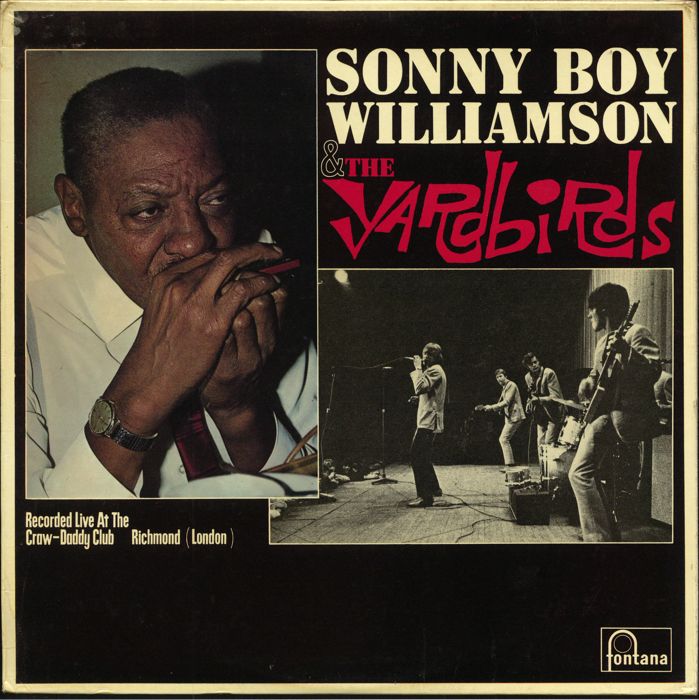

Like caviar with brie on a piece of dark bread, James Cotton was good from the first to the last bite and is always remembered these many years later with an incredible delight, but my favorite harmonica player is Sonny Boy Williamson who was dead five years before I heard of him. I wanted to learn the harmonica and Tony Glover—his how to play the harmonica book is the best—told me that Sonny Boy Williamson was the one to listen to. At the record store when I looked, there he was with the Yardbirds live at the Crawdaddy in London in 1965 a few months before he died.

I never learned to play the harmonica well—sometimes I’m really good, but you can never count on it—yet I must say that I have never enjoyed myself with a performer like I did with Sonny Boy who I got so close to that I went out to the edge, the end of existence following him, a wise poet, as he went taking sound beyond the point where you can hear it, but it is there yet disappearing in the silent shimmering present.

For forty days and forty nights, shortly after I bought that album, I camped out on a mountainside, fasting, sometimes eating a handful of brown rice I kept soaked in a bowl, and sometimes I picked berries in the forest. One day I washed my only clothes in a stream, and then it rained for days. I remained naked playing the harmonica inside a dripping tent where daddy long legs kept crawling in, I guess in search of prey along the creases of the tent. I did get this blues song out of it as it came to me playing the harmonica:

Daddy long legs hanging upside down my door

Daddy long legs hanging upside down my door

Came to tell me you won’t be back anymore

Floating floating like a drowned man on the sea

Floating floating like a drowned man on the sea

Now it doesn’t matter if all the waves come cover me

Don’t leave me, baby, I don’t know what I’ll do

Don’t leave me, baby, I don’t know what I’ll do

I can’t leave this place, there’s not one door to walk through

When you’ve filled your teacup one tear overflows

And all your joys rise past their brims spilling you to sorrow

Ah but you just wipe as you weep as you wipe up the mess, lay your head upon the table

Daddy long legs go away from door

Daddy long legs go away from door

Once you know what the truth is, you don’t have to hear it anymore

The last stanza I added several years ago when I began to learn to play the guitar. I’m not very good at that either; my attention span is short and a call or a book or a thought will call me away before I know what I am doing. It took me twenty years to write my novel. But everything comes in time as long as there is time. Which is the rub today. I have spent a good part of my life trying to write poetry that will stay, like words etched into a rock. But it looks like the world as we know is not going to be here that much longer. As animal and plant species become extinct so do human languages. While bully languages like English, Spanish, and Chinese are taking over, it is heartening to look at a language like Berber in northern Africa where French and then Arabic tried to beat it to death, but there it is yet, Berber. Three cheers! It just won’t give in. Who knows what lies ahead? People may still be speaking English, but in a world where everyone is so busy escaping rising water will there be time for a painting or a story or poem?

Is it ever too late? Voltaire began to learn Greek in old age. I’ve already studied Greek, but have all but forgotten it—If I live I plan to read the Iliad and the Odyssey through my eighties. It is good to be shut in because it makes a routine fit into the day. Nothing and no one to call me outside, no other job or poetry reading at the moment. It is sunny. I’m going to go up to the roof in a minute with my guitar, and I think I am going to put a harmonica in my pocket. Today might be the day when I begin to really play.

…

…

…

…

…

Although it is practically impossible to do, I flunked out of Temple University in 1969—I never went to class and I was drunk all the time. Still I was a little embarrassed and taken by surprise. I got a job as an office boy in an insurance company near Independence Hall filing stuff. A secretary there, whose name was Barbara Mikesell, invited me to come to her commune in West Philly near the University of Pennsylvania. She said they were a religious commune, and if I attended their evening meetings for just one week, she assured me that I would see the light. Who doesn’t want to see the light? It was a house shared by both men and women, maybe a dozen or so of them. They had a leader whose name was Sun Myung Moon who lived in Korea, but was coming to the States soon, and they were very excited about it. They could not have sex until they were married; this is what he told them. They also didn’t drink alcohol, smoke pot or cigarettes because he told them that too. But everyone was sweet teaching me to see the light. On the 7th Day when I didn’t see it, however, they were disappointed and told me not to come again. At work, Barbara was not welcoming either, but she quit shortly after. I remember she had a map of the world on the wall with thumbtacks for every commune they were starting; and even though there weren’t many, they were all over the place like Buenos Aires and Sydney, Australia. Barbara Mikesell went on to sit at the right hand of Sun Myung Moon; she became powerful, and he and she controlled a little part of the world for a little while.

In the early 70s, there was a sufi who lived in a house near the University of Pennsylvania, whose name was Baba something or other—I don’t remember—I’m sure somebody does—so I’ll just call him Baba, which is what everybody did. He was supposed to be 140 years old. Every Wednesday night he gave a sermon and the place was packed with Philadelphians who gathered sticking their heads in at the doors. His followers carried him down the steps and set him on a bunch of pillows in front of us, a tiny man with a gray beard who reminded me of a queen bee with all her drones attending. He never swallowed his saliva but spit it into a pewter bowl one of his followers held. The rumor was he never ate or drank, yet he spit so I doubted that. One night he told us about the time he saw God. He did things like pray for a year with his eyes closed, and fast in desolate places like the Sahara Desert. He spoke in Arabic while a follower translated. When he told us how he saw God, I didn’t understand him, and was really disappointed that I lost something in the translation. After he finished, some of the congregation were allowed to approach and ask a question. When I finally got a turn, I pressed my palms to my heart. ”Do you have anything to tell me, Baba?” I reverently asked. ”Cut your hair,” the translator told me curtly: “You look like a girl.” Those were his only words.

In 1973, I went without pot or drink while I was doing yoga, Anananda Marga, to be exact. There was a guru attached whose name I don’t remember, but he had a wife and kids, and followers who would do the baby sitting, and bring his wife tea and goodies, in fact. I attended meditation classes that always began with asanas. For someone as stiff and tense as me, it was hard to even do the simple sitting, but I persisted. It was always stressed that we must work to be calm at our centers and it was also stressed that we had to read the Baghavad Ghita. “Read the Bhagavad Gita!” somebody was always blissfully commanding. I had the book already; it had been given to me by some Hare Krishnas—the Holy Rollers of the East—when I visited their ashram at dawn in North Philly—Ahhhh! is there anything like singing Hare Krishna to the rising sun? I did what I was told and struggled to understand the Bhaghavad Gita, my first religious book—I’d been raised a Methodist and had heard scripture at church most of my life—but now I actually read the Gospels too—the Sermon on the Mount!—and then Lao Tzu and Buddha’s Dhammapada, which I still, sometimes return to, just like the Gospels. The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky was the culmination; and when I finished it, my life was definitely changed; I saw that I was but a drop in the ocean, and for the first time in my life I understood that. And the Bhagavad Gita, by the way, I found out later on in the group I was in, out of all of them, I was the only one who ever read it.

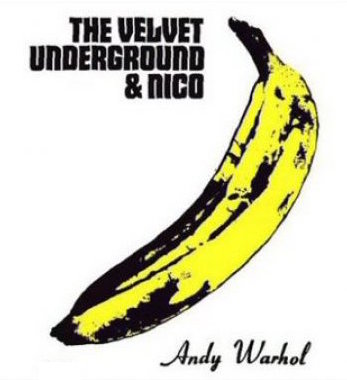

Writers of course can be gurus. When I got to the East Village in 1979 people might be surprised to know that Ted Berrigan was the guru and not Allen Ginsberg. Ted certainly had his disciples, and he was a presence, not just in size, but reputation. I remember it was Dennis Cooper who told me that Ted was dead. I was walking down Saint Mark’s—this would have been July of 1983—Dennis was sitting at a cafe—there were outside cafes on Saint Mark’s back then. “Don, Ted’s dead,” Dennis said with a very sad expression. I asked, “Ted who?” Dennis looked like I hadn’t heard him. But the idea that Ted Berrigan would not be there in the East Village had me dumbfounded. Ted once said to me, “You can take a poem apart and put it back together again like a piece of furniture, every word can be moved, sanded off a little and put back where it was or maybe you want to look at it in another place at another angle.” Though I didn’t think much of it at the time, no truer words have been spoken. Lou Reed was my guru through the Banana Album especially until Loaded. In late 1960s lingo, I might say, “Bob Dylan took my cherry, but I left him for Lou Reed.” What did my new lover teach me? Well, that it is OK to repeat words, repeat sounds, to talk like you talk because if you are truthful about it that will be illumination. I never met Lou Reed. My friend Bernadette said he was a narcissist who even brought his own sound equipment to his reading at Saint Mark’s, and he was very rude about it. But I will always be grateful to Lou for letting me know that I’m enough.

…

…

…

…

…

…

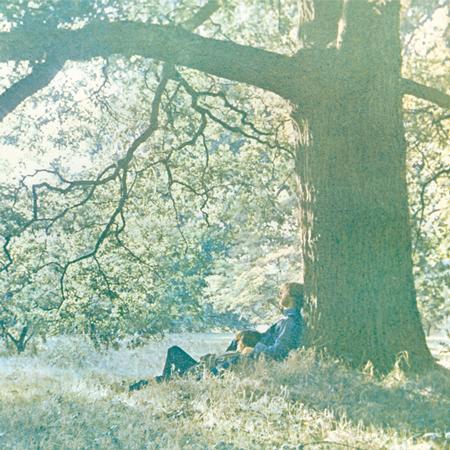

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again—writers one way or the other keep saying the same thing over and over until they’re dead—I loved Yoko Ono before John Lennon did, and because love is selfless when it comes to Yoko, I was really very happy when I learned that they had met.

In my sophomore and junior years of high school, I had to wait an hour after class until elementary school let out so I could take the only school bus home to the South Mountain. I hung out in the library. And, let me tell you, the Cornwall High School Library was something back then. The librarian, Mrs. Troutman—she had been Miss Biddle for decades—”Not of the Philadelphia Biddles,” she’d say—Miss Biddle got married at a later age, but kept riding her horse at the Quentin Riding Club like she always did so she was, a tall woman, always a little bow-legged—Mrs. Troutman saw to it that students and staff had all the major newspapers. Every day the NY Times, the Washington Post, the Philadelphia Inquirer, even the Harrisburg Patriot and the Lancaster Intelligencer were hung up on those thin long slatted posts for anyone; and there were weekly and monthly magazines as well: Newsweek, Time, the New Yorker, the Saturday Evening Post, and the Atlantic Monthly come to mind at once. Mrs. Troutman supplied all of the books that wound up the NY Times best seller list too, though students were barred from the likes of Candy. I remember Mr. Burkholder, a math teacher, returning Candy, slamming it down on the counter and saying to the smiling librarian: “That was the most disgusting book I’ve ever read,” as I thought to myself: “Ah, but you read it.” I had had a copy of Candy, but Allen Gill’s mother burned it when she found that Allen had hidden his borrowed copy in the laundry—why and what was he thinking?—if indeed it happened the way he said it. I was lucky to have parents who, as bad as they could be, never censored a thing that I read.

Among all the magazines, papers, and books, I always made a point of reading Time Magazine while I waited for the bus, and it was there I met Yoko in an article about a performance she did at Carnegie Hall—this would have been 1965—where people came up from the audience and cut off a piece of her clothes until she was naked on stage. Yoko had me at naked, and from there on out I was always a fan of hers and even sometimes a follower.

Don’t tell anyone, but I was glad the Beatles broke up and John went off with Yoko. The albums they did together are among my favorites. Her Plastic Ono Band that she did in connection with John Lennon’s I first heard on acid. I forget her name—she lived at the Weatherman’s House in East Lansing—which was a very paranoid place because the Weathermen were always cleaning their guns and waiting for a shootout with the cops—I mean the pigs—which never happened—it was like they were playing Cowboys and Indians as young adults just like they did when they were kids. Anyway, we were tripping and—I’ll call her Mary—put on Yoko singing Why? with John Lennon on guitar and Ringo Star on those relentless drums, and as the saying goes, it blew my mind and again I fell in love. For me, Yoko Ono is the eye of the storm: When I heard her sing—most would say scream—I really felt at peace; I got all fuzzy and warm.

Shortly after, John Lennon released Cold Turkey as a 45 with Yoko on the B-side singing Don’t Worry, Kyoko, Mommy’s Only Looking For Her Hand In The Snow. There was a pizza parlor in East Lansing that had a jukebox. I would stop by sometimes to play both John and Yoko singing. It got to the point the owner would see me and say, “Not you again.” Cold Turkey was bad enough, but one day, as I played Don’t Worry, Kyoko again and again, customers began complaining. This was great art I thought and wouldn’t stop even when a table of customers began threatening me with violence. In order to stop a riot, the owner came out and pulled the plug, and that was that. Silence. Like when people threw tomatoes at Dame Edith Sitwell reciting her poems through a megaphone, as much as I loved Yoko Ono, I could see others did not. I had never seen any other artist have such an effect on anyone. Yoko Ono was number one. I said to myself, “What helps to keep me sane, drives others mad. If I want people to like and read me what can I do about that?”

A few years ago, I was at a party where Yoko Ono was as well. As she was about to leave, I approached her and said as earnestly as I could, “Yoko, I love you very much.” She looked really scared—she’s such a tiny thing—and ran away at once.

…

…

…

…