…

Guatemala Notebooks

or Trying to Understand Something

for Pat who asked me when he left

to keep this journal in his stead

The same symbols keep repeating themselves.

…

December 9, 1990—

I got you into the cab by ten and you were off to the airport. By nightfall you’d be back in Tacoma, adventure over, while I had to get back to Santiago by four: Esteban would be there waiting with the canoe and I wanted to be in it rowing. After Tikal, the ear infection, the food poisoning, the traveling and the annoying military presence, I was anxious to get back to the beauty and the quiet of the house I’d rented. The buses still weren’t running; the price of oil was rising even higher the señora told me at the Posada Real Hotel, but there was no problem; she assured me that she could get me a cab for one hundred quetzales. That, I said, would be wonderful. Tell the cab to pick me up at eleven-thirty, I told her and leisurely walked through the city of Guatemala to have breakfast which I leisurely ate, then strolled back to the Posada Real by eleven-thirty to have the señora tell me that the cab company she usually called was closed because of the rising costs. She’d called another company: they wanted five hundred quetzales. A hundred bucks to go to Panajachel! It was a two dollar bus ride! But the buses aren’t running, the señora reminded me. Did I want the cab for five hundred quetzales? No. I thanked her for her trouble, grabbed my bag and took off bargaining my way down the street until I found a driver who’d go for two hundred and seventy-five. I had to get to Panajachel: the boat for Santiago was leaving at three and it was now noon: I would be in Pana by two, able to do all the things I wanted to do—I sat back, relaxed as I left the city limits and opened the letter that you’d handed to me before you got into your cab:

12/7/90

Dear Don,

It’s 6:10 and I just went in to check on you. You’re sound asleep and I’m hoping the medicine is helping. We may have liked the other hotel better, but at least this one was near a pharmacy and you could get some anti-biotics.

Excuse me if my handwriting gets progressively worse. Without a word of Spanish, I got the owner of the bar to open it an hour-and-a-half early and I’m on my fourth “CER-VAAAH-SA!” Of course that was after the two CUBA LIBRES I had in the room. (The bartender just came in to collect for my fourth beer; he’s been letting me serve myself now!)

I really want to share some thoughts with you, but as always the timing is way off. I’ve been thinking about the Santiago massacre. I know it had a deep effect on you and on me, perhaps to a lesser extent. I set boundaries between myself and “other people’s problems” because I have to, to do the work I do as a therapist. If I didn’t know how to detach myself emotionally on a daily basis, I’d truly go nuts. I’m learning to survive the care-giver role.

Part of my fear of getting involved in an issue stems from my professional training, but another reason is my plain fear in and of itself. This makes me so ashamed when I think of how Esteban’s people were brave enough to close the market no matter what reprisals may lay ahead. Only I hope I would feel so brave if it were actually happening to me.

It is not “their” problem; it’s “OUR” problem, if you think in terms of all human-kind being one sharing the same ecology and planet. If we don’t think as “one” then the big-guy is always going to be beating up the little-guy. I like, admire your willingness to get involved.

But Don, you sometimes scare the shit out of me and I have to tell you about it! Today on our walk you were having a talk with the French Guatemalan in front of the tour guide. I don’t think you know their political viewpoints, but that you assume everyone feels the same as you. As Omar told you, all men here are required to “enlist”. That 13-14 year old kid was probably in training and the driver of the van was also probably a soldier, happy or not. One gets brownie-points by being a snitch to others with power. Who are you to them but a gringo with a possibly “unfavorable” opinion? Don, you don’t know who you’re talking to, and sharing your impressions here is fool-hardy, potentially very dangerous, and doesn’t help your goal. It’s not the same as speaking out back home where you’re supposedly protected. You have no rights here where death squads abound.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t get involved, but I do want you to consider your methods. A first point would be to see if Esteban is willing to take the risk by talking to eye-witnesses and setting up interviews with you. I believe he probably would but you must check that first, and not assume he does. You must consider his safety and whether you can offer enough safety and anonymity for him.

If Esteban does want to risk exposure, perhaps you should use whatever influence you have in NYC or call the photo-journalist and put her in touch with the eyewitnesses you could supply. That would do more good than loose chatter, but even still Esteban has to be considered first, and he has to be in charge of his own risk factor. Otherwise, Don, you could be responsible for a horrible tragedy of your own making.

I’ll do the following two things. First, I’ll call on Monday to talk to our newspaper editor personally. As I’ve already mentioned, he’s a friend of mine. Grace and I have also subscribed to and have a membership in the organization “Central American Peace Initiative”. I will call them with an article for their next publication and to spread the truth.

Don, this is the best vacation I’ve ever been on. Not the most relaxed, but the best. I never expected Guatemala to be an easy vacation. Travel in the 3rd world never is, I guess. But I didn’t expect it to be more emotionally difficult than physically.

Guatemala is an experience in itself. A wonderful experience. It’s also been an experience for me in terms of putting myself and my problems in perspective once again. I came here hoping to gain some answers to my dilemmas. Perhaps I have; perhaps I haven’t. I do now once again realize that my life’s dilemmas are insignificant in the realm of all things. There is something more important than my personal happiness, tranquility and ego-satisfaction. Thank you for suggesting Guatemala.

Love, Pat

P.S. I wouldn’t immediately trust the photo-journalist either.

P.P.S. I KNOW YOU’LL DO WHAT YOU FEEL LIKE DOING. It’s now 7:45 and my sixth CER-VAASA has arrived. The bartender just told me the chef left, I can’t get dinner here and there is no other place in town that’s open. That’s Guatemala. Oh well, at least I’m drunk! (and not too hungry)

P.P.P.S. Do you know that no one else ever came in to the bar or restaurant all night? Do you think they ever had a chef?

I put your letter away and thought about what you had to say as I looked out at the changing landscape: cornfields and mountains flowering. Your carefulness and my carelessness had struck a happy medium on our nine day trip together but now that you were gone I had to watch it: my mouth. My skinny old driver and I were climbing up the mountain; I knew we’d get to Panajachel on time but somewhere toward the end he took the wrong turn and there we were lost on a road full of holes, or there was no road at all, the macadam gone, cratered out, a ride of lurches, swerves and bumps that often overlooked looming precipices. Yikes! Here comes a cow! Oooo! Here comes a bus! Ow! Here comes a bike! I held on to the back of the seat and looked at my watch. It was after two o’clock and we were still way up in the mountains coming down. By the time we got into Panajachel my minutes were rapidly diminishing. I ran to Marion’s—just to say Hi! is there a place in town where I can use my credit cards to get money if something awful happens and I want to get out fast? Marion laughs and says that I could use my credit card at the bank and added for me not to worry. Hadn’t I heard the good news? There were all sorts of Human Rights groups in Santiago over the weekend. The military is leaving.

Good, I say and off I go running to the boat for Santiago. It’s full of Indian men. I don’t see a woman. I sit inside toward the front looking out over Lake Atitlán toward the volcano of San Pedro where my rented house is an hour off in the distance. A young woman with long straight brown hair and a soft pretty face without makeup came in and sat down in the seat behind me. We were the only foreigners on the boat, and she the only woman. I suspected that the massacre had scared off the tourists and I turn around and mention this in English to the girl sitting straight up behind me. She’s from the States and she agrees: Yes the massacre has scared off the tourists definitely. She’s a nurse in Santiago and San Pedro and goes from village to village encouraging the Indians to get vaccinations. Right now she has dysentery and can’t wait to get to Santiago to medication and home. It’s quarter after three and the boat hasn’t started. She says the boat might go to San Pedro first, but she wasn’t sure, she couldn’t get a straight answer out of any of them. If San Pedro came first that would be a half-hour more: it would be getting dark. Inwardly I moaned. I told her the guy told me we were going to Santiago. She said that meant nothing. She looked disgusted. How much did he charge you? she asks. Five quetzales, I tell her. The Indians pay two. They usually charge the tourists ten. Last week they charged me ten, I say: I guess this week I’m not as much a tourist. Because she was a nurse she got to ride for free. Her name was Laura, she was not much more than twenty-one and she was pretty. I asked, Do the men here ever hassle you? All the time, but I just keep walking. I said: I bet it’s not as bad as Mexico. No, it’s not as bad as Mexico, but do you know where it’s the worst? I didn’t. Italy.

We left the dock at three-thirty and it was hard to tell whether we were going to San Pedro or Santiago because the boat kept swerving back and forth. It was like the guy at the wheel was trying to make up his mind and at times the guy at the wheel wasn’t steering, he’d let go and talk to his buddies and the boat would be standing still bobbing in the darkening waves. I noticed that the guy who’d taken my money was pouring agaurdiente into the Pepsi-Colas and I said to Laura, I think they’re drunk. Of course they’re drunk, she said. We bobbed back and forth and I asked her if she’d heard if the news of the massacre had gotten back to the States. It was in the The New York Times, but she didn’t think it was on television. I said I hope with all the Human Rights groups in Santiago the truth will be told. Was she in Sanitago during the massacre? No, she’d left the day before because she had had a nightmare. People had been getting shot the whole week before. Her cook was the town gossip and if someone got shot at four AM she heard about it by seven. The day before the massacre she’d gone to the public phone and as she dialed two fifteen year old soldiers stationed themselves on either side of her with their M-16s resting on their chins ready to listen to what she said. She wanted to pull their triggers and blow off their heads, but she stood and stared and waited till they left, and then encouraged by their leaving yelled in Spanish to her friends who were waiting across the street, I’m sick and tired of these fucking soldiers! Her friends who were Guatemalan became alarmed and told her to be quiet. Her house was next to the army barracks. She had a nightmare that night and left the following morning. I’ve been lucky this trip, she says: even with the dysentery I’ve been losing weight.

She asked me what I did. I don’t tell her I’m a poet or that I paint towel and bed sheet showrooms. I tell her I’ve spent the last three years of my life fighting to save a community park in New York City called La Plaza Cultural that was slated for a HUD 202 housing project. We went to federal court and stopped that because a judge said that HUD must follow its own regulations and not put all its assisted housing in one section of a city. There’s already a lot of low-income housing in the East Village where La Plaza is. “Why don’t you put this project on the Upper East Side where the rich live?” the federal judge suggested. Now the city is trying to evict us. Every time I think it’s over, something else happens, a little victory followed by a little defeat, a little defeat followed by a little victory. So far it’s still a park.

She says, You’re luckier than I am: being a nurse in Guatemala is one small defeat after another. Our boat enters the inlet toward Santiago. We are going to Santiago. I point at a rich person’s house being built on a passing promontory and ask, Do you think when the soldiers leave more tourists will come here to live? She motions to the Atitlán volcano. Up there in those mountains are beautiful villas that no one’s been in for ten years. If it was your place and the soldiers left, wouldn’t you come back?

Off in the distance to our right I saw my house. I’m living over there. I point trying to see if Esteban’s children or Maria the pup are out but I see no one. Laura looks at my house passing near and yet so far over the waters on the volcano’s side. She says, You are very far from town. The soldiers would never come out there to kill you.

I ask her off the wall: What do you think about the Evangelical Church in Santiago? You hear about the Catholic priest being shot but you never hear about any of the evangelicals getting it. Do you think the Evangelical Church is a CIA front?

She shook her head. They’re both anti-communist. The Evangelicals tell the Indians that life is to suffer and die and then you go to heaven. Evangelicals don’t complain and that helps the government.

I think they’re rude, the way they broadcast their services over loudspeakers assuming we all want to listen. I can hear them across the lake.

They are loud, she said.

When we were nearing the dock, I was suddenly sorry that we didn’t have more time to talk. I wanted to talk to Laura about what she knew and I wanted to talk to Laura’s cook, but all Laura wanted to do was get to her medication and was gone in the crowd off the boat.

Esteban was there waiting. He had my groceries already in the aluminum canoe: tomatoes, carrots, cheese, tortillas, scallions, bananas, candles, agua minerals, but there were no pineapples or mangoes because—Esteban tells me—there are no buses coming up from the coast.

There were no buses from Guatemala either, I tell him. I had to take a cab. Two hundred and seventy-five quetzales! Esteban looks at me flabbergasted. There are no buses in the city. Everybody is hitchhiking. It’s crazy. I asked Esteban to wait for me and hurried up to town, found an open pharmacy. I explained my ear infection to the pharmacist: I could hardly chew, there was pain, I’d taken drops and antibiotics but it lingers: he gave me a sulfa drug to spoon out every eight hours and then I was back down the hill to the dock into the canoe, me in the front, Esteban in the back. We push off into the stormy lake.

I say, over my shoulder as I row, Esteban, I heard there were a lot of people in Santiago over the weekend. I heard the army is leaving. Esteban says, Yes, the army is going. There was a big demonstration on Saturday. People came down from all the villages with posters and pictures of relatives and friends who’d been murdered by the soldiers. There were thousands of people and journalists. There were a lot of cameras. That’s good, I say, then the whole world is watching and doesn’t need to hear the story from me I think to myself sadly shaking all the dead off of my shoulders.

The waves were getting rough, big ones and I—rowing in front—was splashed and soaked. We were hitting the waves head on. Esteban was crossing the lake going forward slowly following the shoreline on the east side of town out toward the Refugio del Poc where I looked to see if I could see the flightless duck. I see black ducks, a flock of fifteen, bobbing outside the reeds that we were passing and I ask, Are those poc? Esteban says, Those aren’t poc, those are ducks.

At the little island we cross into the lake, working our way over I yell back to Esteban over the wind and water, I don’t know what I’m doing! When should I row? Esteban tells me not to row when the wave’s coming at me but after it goes which is what my instincts had told me to do. I must follow my instincts more I said to myself and I rowed. It was getting dark. The kids ran down the steps and little black Maria hopped and barked. Cruz, Juan, Pelipe and little Domingo helped to carry my things up the steps. I thanked them and they continued up the steps to Esteban’s. I lit candles to put things away, unpacked, and then sat on the back deck brooding drinking a beer smoking a cigarette. The winds died down. You were gone. I looked up at the constellations alone.

…

DECEMBER 10—

What a difference a day makes. I got up at six-thirty happy to be home and watched the sun rise over San Lucas road and the shimmering lake. I washed the windows to improve the beautiful view: there were so many smashed bugs it was a blur. I swept the floors and decks and put everything away. It was pretty bare, but then the books I need do appear—notebooks first to write, then the dictionary comes out to be sure I know the word for “hole”. “Hoyo” was the word Esteban used when I asked him where I could put the garbage—“Up on the hill in the hole.”—I knew where the hole was, but I wanted Esteban to know I could and would carry my own garbage up. I tell him I know where the hole is, I was up there and I saw a dead snake. I killed it, Esteban says. I knew he did and I tell him, You don’t have to kill snakes for me, I’m not afraid of snakes. I pointed to the rat walking above us in the rafters: snakes like to eat rats. Rats like to eat your corn so the snake helps you, you shouldn’t kill it with your hoe, Esteban. I’d rather have the snake above my head right now than a rat. Esteban nods at my talk but I fear the next snake will be a dead snake that comes along.

In the midst of giving the bedsheets a shake in the air, I hear a crash—a yellow finch smashed into the window and now was on its side in the shade of the papaya on the wooden deck, legs moving in and out bicyling. There was nothing I could do, but leave it to its gasps. Later it was still there on its wing helplessly out of it and I thought, if Maria comes along, she’ll eat it. I went to pick it up, but the finch jumped to its feet, up onto the step. I let it rest there and kept an eye out for Maria, then passing the finch for the kitchen it flew up into the tree over the hammock which I swung in for awhile and watched. What a happy morning! In the hammock reading, looking up from my book lost in the volcano clouds or watching Esteban planting flowers along the steps above the house while his three year old son, Domingo—chubby and barefoot and dirty—plays at his side sometimes shaking the blue and red strips of plastic Esteban has tied together on a stiff piece of wire, a simple colorful toy. Domingo and Esteban were chatting in dialect, a continual conversation. I’d talked to Domingo earlier in Spanish and he’d not understood a word I said looking at me like a quiet idiot, but in Tzutujil Domingo was talking up a storm: the little kid is smart. If Domingo wants to help dig a hole or water the flowers Esteban patiently lets him help, though he could do it a lot faster by himself. At one point Esteban was walking up the hill to his house to get more flowers holding Domingo’s hand, following his son’s step and talking to him as they went. Later coming down Domingo was carrying a little lancha with two oars that Esteban had made for him. In a little while he’ll be rowing across Atitlán. I want to take a picture. Domingo hides behind his father’s leg. I give him a banana which he takes, peels and eats. I tell Esteban it’s great that he never shouts at his children. “Dogs shout—they shout all day and they shout all night.”

I bathed in the lake with my goggles on. I saw a yellow fish. I swam back and forth along the edge where it suddenly gets deep at the end of the dock where all the underwater plants come floating up. I see Esteban on the other side of the dock heating up a tar-filled pot over a fire. What a picture! I go to get my camera and return down the beach. Among those light volcanic stones, Esteban looks up at my camera and it’s not Esteban! I’m sorry, I say, I thought you were Esteban.

I’m Santiago, Esteban’s brother.

You look like each other. Do you mind if I take your picture?

Not if you send me one later. Santiago dips strips of rags into the boiling tar and then pushes them into the cracks of his lancha with his steaming machete, then he pours a ladle of tar over the ragged crack and smooths it out.

Esteban comes down with Domingo and rests in the shade of some poinsettas watching his brother. Domingo shakes his red and blue plastic.

In a little while I’m going to row Domingo into town. I want to have supper with my wife, Esteban tells me.

I don’t mind if you stay in town tonight. I’m not afraid of the dark. I was raised on a mountain and I know all the sounds. Stay in town tonight with your wife.

I like it our here. It’s quieter than in town.

Well, if El Norte starts to blow, don’t worry about me. Tomorrow sometime I do want to row into Santiago. I want to walk to the army barracks. I want to see where the massacre happened. Will you show me the road? You don’t have to go. Are the soldiers still there?

They are still there, but they are leaving.

When?

Esteban and Santiago don’t know. Soon.

Now it’s evening, about quarter after seven. El Norte is really bringing the waves against the beach—all is dark outside, no stars and in the cabaña below two fisherman have come in out of the rain. I hear them talk. I’m sure Esteban will not be back tonight.

Around sunset I was reading the first chapter of Genesis in Spanish when out in the tall grass I heard a scream. Up flew a hawk swooping past me with a shrieking yellow finch in its talons. Was it the finch from this morning still a little slow? Poor finch I thought silently being devoured but I didn’t take it as an omen, it was life going on.

Tomorrow’s list: candles, more rolls of film, and I hope a pineapple.

…

DECEMBER 11—

The lake was tranquil when Esteban and I rowed in. I was looking forward to walking to the army barracks, but as soon as we landed Esteban tells me today is too dangerous—peligro—today they are stopping people and looking at their papers.

Fine. We can go another time. Let’s go to the market.

On the long veranda of the municipal building in the windows of all the rooms overlooking the market are posters with the photos of all the people in Santiago who’ve been murdered by the soldiers over the last ten years. The front of the municipal building is crowded with people looking at the photos. Mostly it’s women, baskets of market produce on their heads, young girls. Esteban and I slide among them and walk along the front looking at the snapshots, the high school photos, the poses by the lake by the boat. This woman looks like she was a school teacher. This man stands proud in his colorful Indian dress. This is a kid, a little kid, ten. This is a priest, mostly they are men, young men. A woman points out the photo of a man: Diego Mendoza Ratzan. The date he disappeared was 15 Febrero 1983 and I think to myself, What was I doing that day? He looks dignified in his suit and tie, an older man, fifty and not necessarily Indian. But the woman who’s pointing’s an Indian: He was my uncle, he worked for four years with the Ministry to save the Poc, the little black duck. One day he went to work and never came back. He was a nice man who wanted to save the poc.

I look at the photos, walk along the faces, the hundreds of dead the decade of Reagan.

Esteban points to a photo. This was my brother-in-law and friend Felipe Vesquez Tuiz who was shot in July of 1981. He liked to play guitar and sing the songs of Maximón.

Why did they kill him?

He didn’t like the soldiers and the soldiers didn’t like him.

On every house over every window and every door are hung black bows made from black garbage bags. They’re everywhere you look and large ones are stretched with wire over the streets. In this mourning there is a great unity, in the black bows made from black garbage bags a great dignity. It’s very quiet. I’m not sure what’s happening, but the soldiers haven’t left.

…

…

DECEMBER 12—

All along the shoreline

it begins with rocks

that gather into bushes

and go up

The clouds come down

from the volcano tops

Mostly it’s silence, the sounds that are

have been here a thousand years—The oar into the lake

a heron—the wind—a wave.

From where I sit a mile across

Santiago’s mostly hidden

by the protruding foot of San Pedro

stepping out into the water

whose steep hills have been

hewn into cornfields now brown

and in them starting cabbages

The sky is blue

The clouds engulf

This lake is like the lap

of some maternal goddess

…

…

DECEMBER 13—

Today I rowed with Esteban toward the hill facing the house across the bay toward Santiago, where all those white rocks come down, which is actually not part of San Pedro’s slope, this mound of tree, cornfield and coffee bean was once the capital of the Tzutujiles, a city of mighty warriors, Chuitinamit, that Pedro de Alvarado—after much struggle—burned to the ground.

Esteban and I canoed our way among the white rocks and there was Adrian, in a cornfield, looking for artifacts. Just to pass the time, Adrian tells me, as he lays out some pottery shards. I met Adrian two days ago at the Hotel Chi Nim Ya and he told me he’d tell me what little he knew about the Santiago massacre. We sat in the sun on the hot white rocks. Esteban rowed off leaving us to talk saying he’d be back in half an hour.

Adrian tells me that for a long time things had been working up to what turned out to be the massacre. Last July a band of masked men robbed a bus on the San Lucas road and shot four of the people on it, calling them out by name. It was probably soldiers. A week before the massacre the telegraph operator was pulled out of his house and shot. They say it was the soldiers who did it, but Adrian has his doubts: the telegraph operator had been overcharging people and not sending messages, and most of all he’d been getting women pregnant. Adrian heard the shots. There were seven. He thinks Santiago people did it. People are always blaming the soldiers, but if you hang around long enough, you notice in the town itself there are a lot of vendettas. The Wednesday before the massacre two cops who were shaking down people on San Lucas road got shot in their arms by someone up in the hills. And about a month ago, foreshadowing the doom, the cofradia, the priest who looks after Maximón, Santiago’s village god, was shot down in front of the deity himself. Maximón was covered with his priest’s blood.

Why would the soldiers shoot the high priest of Maximón? Wouldn’t that just be asking for trouble?

Who says it was the soldiers? It could have been robbers. Nobody ever knows for sure. They’re always wearing masks. Adrian wasn’t standing up for the soldiers. They were responsible for the massacre. A group of them had been drinking in a tienda, and the owner wanted to close, an argument ensued but the owner managed to kick them out. This was around eleven-thirty at night. The soldiers went down the street, kicking in doors, shaking down people. Adrian had heard they tried to rape a widow. People repelled the soldiers, a crowd was gathering, someone rang the church bell, the mayor was there and suggested they all go to the army post together, which they did, but before they could say anything the soldiers fired, first one shot in the air, and then down into the crowd. The town was panicked, full of rumors that hundreds had been killed.

I tell Adrian, I was across the lake and didn’t hear a thing. By then I was asleep. Earlier on my friend Pat and I sat on the porch having a rum and watched a lightning storm over Atitlán Volcano. It’s hard to believe on one of the most beautiful nights such a horrible thing could happen.

The soldiers dumped the bodies in the town square in front of the Catholic church where they would stay the next day photographed by the journalists. Nobody can move a body until a magistrate has signed the papers. Sometimes a body will be in the street from one day till the next, and you’ll have the screaming widow and the children and the friends shooing the flies off of the corpse around which a gawking crowd revolves. The way they let the dead in the street is the most barbaric thing about Guatemala, Adrian says, but I just got a letter from my mother. Do you know in New York this year there have been over two thousand murders?

Not to mention AIDS, I said thinking of a friend who would probably be dead before I was in New York again. I never thought I’d know so many people who were dead.

Adrian used to live in New York. He worked on Wall Street. He lives in Guatemala for the dry season, October to May. We talked about the Gulf War. Saddam Hussein was created, Adrian says, by the Westen governments for their own profit, a monster that’s now biting them back.

I ask Adrian if he thinks the evangelicals are a CIA front.

Adrian gives it some thought. Well, General Rios Montt was a born again evangelical, and it was Montt who brought the evangelical church into Guatemala, and it was Montt who got U.S. military aid from Reagan after four years of not getting it from Jimmy Carter. Reagan and Montt were friends, who knows? Montt attended Jerry Falwell prayer breakfasts at the White House. Similar natures work together. Montt and the evangelicals prospered with American tax dollars, payment for killing Guatemalans accused of being Communists.

I mention that now that the soldiers are going maybe tourists will come to develop around Santiago. It is so beautiful here, I tell Adrian, that many people would think about buying land, but this land belongs to the Indians. Adrian has been thinking about buying land, but he also feels like I do. This land belongs to the Indians. Adrian has his doubts about tourists taking over Santiago. Santiago is an Indian town. He points up the hill beyond the cornfields to an abandoned house. It was once opulent but now has no windows or doors. Drug money had built it. Most of the big houses around the lake were built from drug money. The hippies who came here in the sixties became conduits for everything coming up from the south and some of them got rich. Even now all around us are drugs. Here there are no limits, you have to watch it, there’s nobody here to tell you to stop. That’s what happened to the people up at the house. I looked up the hill to the doorless house. Adrian says: The hills are full of Indian spirits. This was the city, Chuitinamit, and the Indians here fought like crazy against the Spanish, and the Spanish couldn’t get them either until they got the Cakchiqueles to help. They came over from Panajachel three hundred cayucas full and they destroyed Chuitinamit and Alvarado moved the city to what is now Santiago. Don’t buy land on this hill, Adrian warns: here white men go crazy. Here there are no head doctors because the Indians are very sane, but the Indians do get sick: bronchitis, hepatitis, lice, there is filth, oh, and soon there will be cable television.

Cable television?

Adrian shrugs, the world is changing and Santiago will change with it. They must. Let’s hope.

I point across the lake to the refuge of the poc and ask, Does the poc live there or not? I’ve seen ducks, but were they pocs? I want so hard to believe out there in the reeds a poc breathes.

They were ducks. There are no pocs. The Indians and the black bass ate them, but don’t be depressed, Adrian says, the people in Santiago are happy. People are smiling in Santiago. I’ve just been up north in the mountains. You go from village to village and everyone is frowning.

Adrian points toward Panajachel and there in the horizon is the profile of a sleeping Indian clear as day: flat forehead, nose, chin, neck, chest flowing in the mountain. The Sleeping Mayan, Adrian calls him. Sleeping Mayan, I thought, wake up.

…

…

DECEMBER 14—

Market Day. It was packed. As Esteban and I are at the higher end of the market looking for avocados, I notice on the roof of a building a soldier standing guard who pretends to be shooting people in the market. When he’s pointing the rifle the other way I snap a picture. A cop on the ground is laughing. They both think it’s funny the way he’s been mowing us down. My picture taking is making Esteban nervous so I stop.

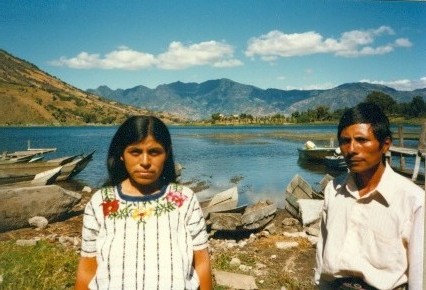

Esteban is dressed up today. Clean long-sleeved tan shirt, village pants of white and red stripes, the multi-colored belt of great length wrapped around his waist. He’s wearing shoes, black loafers. I told Esteban I’d take a picture of him and his wife. Partly I wanted to see what kind of house Esteban lived in, but we aren’t going to his house, we go back to the boat and Esteban goes to get his family. He wants his family by the lake. I wait. Through the dry brown corn she comes, white blouse embroidered with flowers, a basket of food on her head, dinner for Esteban and the kids back at the house. It would have made a great picture, Esteban’s wife coming through the corn, but it was facing the sun. I shot Esteban and his wife against the lake: stiffly they’d pose like an old time photo. They have nine kids though a few days ago Esteban—I thought—told me he had seven. He told me Domingo was the youngest, but not so, here was an even younger one, Basilio, sucking at his mother’s long and much-used breast. She doesn’t speak Spanish, neither do the kids. They say, Sí, but that’s it. I wonder when Esteban and I talk, are we always understanding each other?

As we push off to row home Domingo and Francisca run in the neighboring boat to help push us out, they are having such fun giving us this shove, I reach back to get my camera: it would make a great picture, but I am facing the sun: even if I got the camera they’d stiffen up.

Scorpion in a cup

3:40 PM going for a swim

Let it loose behind a rock

Poison’s her money

she doesn’t want to give it up

…

…

DECEMBER 15—

The day is beautiful. The waves of El Norte crowd the beach. Soon I’ll go down to swim. Pedro is down there now filling the lancha with the wood Esteban and the boys cut. What a face Pedro has: completely open and healthy and good-looking. Sometimes he wears his cap brim to the side like a teenager back in the States; he must have seen it on television. He took his sneakers off and is working barefoot. He’s laid down two parallel sticks of wood about a foot apart on the ground and is laying the other logs across them. When the stack is high enough he takes two ropes and ties them securely to the parallel stick ends and there you have it: a load of wood on his back into the boat. Today is El Norte, Pedro says. It’s a little dangerous. When there’s sun there’s El Norte. After a night of rain there is Choco Mil (I’m spelling this phonetically, it’s dialect, Tzutujil for when the wind is calm.) His brothers Cruz and Juan only cross the lake when there is Choco Mil. They are afraid. Pedro’s been crossing the lake since he was five cutting wood with his father on the mountainside and selling it to people in town. He’s seventeen. I tell him I used to cut wood with my father, he has a chainsaw, I say in sign language using my two hands as though a chainsaw was in them. I say the word, machine. That’s very quick, Pedro says. But dangerous. A machete is dangerous too. Pedro has to get going. He’s going to cross the waves, cross the foam, over toward the island which is a much longer way to go, but because of El Norte it would be dangerous going often broadside the short way into town. The tumbas are dangerous. Tumba which is the word he uses for the dangerous waves means tomb, a somersault and a fall. Pedro now is small, smaller, approaching the island where they are trying to save the poc, now gone.

…

…

7 PM—Dark out. The crickets and cicadas chirr. El Norte beats upon the shore. Just now as I write on the bed in candlelight something falls on my knee from the ceiling and I look thinking it’s a piece of thatch but it’s a spider a little smaller than my hand just standing on my denim knee cap real hairy shadowy and black. But I’m a country boy and I was wearing pants. With the notebook I sweep it off into the dark and continue to write. Today Esteban, Pelipe and Maria and I walked up the mountain on top of the old city of Chuitinamit. We walked along the shoreline from the house into the little woods, then onto the shore again where all the big white rocks begin. This is where Esteban said the land was for sale. It was a pretty narrow plot with lots of rocks, but the beach there was very nice, but not much of a view: you saw a little of Tomilán volcano and the flatness of the eastern shore. We walked up into the rocks. It was tricky at first but then I watched Esteban step and tried to copy his movement. We walked through lots of newly planted coffee trees in the shade of higher trees going up the mountainside into the sun and grass where a path has been cut into the earth by the tread of foot after foot. I was breathing hard but neither Esteban nor Pelipe heaved once. Their ascent was effortless. I stopped in a sunny dusty cornfield to take a picture and catch my breath. I tell them: My father has a cornfield but it’s on flat land. In my country we are used to flat land. Esteban says, Here we are used to this.

The view from the summit is breath-taking. You can look down to Santiago, to Atitlán and Tomilán, the road to San Lucas and across the lake to where Panajachel is with its horizon of the Sleeping Mayan. All about us cornfields have been fenced off with the stones of old Chuitinamit. I look across the water and think of the three hundred cayucas full of the Indians coming with the Spanish to destroy the town under my feet. I wonder looking across the water: What if the American Indians had stuck together instead of turning each other over to the French, the English and the Spanish? Well, I probably wouldn’t be here on this summit looking out thinking about it. We’re up on the ultimate rock where a basin has been cut five hundred years ago to catch the rain. A basin big enough for both of us to be standing in. Everywhere you look, Esteban says, is a beautiful view. It’s true. Then it’s time to go and I jump planning to jump down to another rock seeing as I jump that between me and the other rock is a cornstalk sticking up where I’m coming down. I’m thinking Ouch! and thinking of the cornstalk into which I fall I miss the rock and tumble down onto the ground, knee scraped, but no blood. I get up and say, ¡Dios mio! in a funny way so everybody knows that I’m okay. Pelipe is looking at me with big eyes. I make a face. He smiles. Esteban says, You have to be careful. I say, I should be barefoot like you. Pelipe goes tapping along on things, a born percussionist tapping tree trunks as he walks, and the rocks. At the house I can hear Pelipe coming because he’s always hitting something. I say to Esteban that Pelipe should play the drums for Maximón. But Pelipe adamantly shakes his head that he doesn’t want to. Esteban says: Pelipe takes after my sister’s brother, the one who sang the songs of Maximón.

The one the soldiers shot?

Yes, him.

Why did they shoot him?

They shot him in the market with machine guns. They said he was a guerrilla but he cut wood just like I did. He was a worker nothing more.

I keep trying to take good pictures of Pelipe and Esteban but every time I get ready to shoot, they pose, destroying the wonderful expression that was right before it: I have to be quicker to get them. Esteban is talking about the soccer games he has played all his life as we walk down the mountain on a narrow path edged by grasping cactus. There are games on Sundays between teams in town and there are bigger games between the villages, football games that go back to the Mayan times when they were deadly serious: the losers got sacrificed. Esteban has three trophies and I tell him that I’d love to photograph him with them. He’d like that. I hope this time he’ll let me into his house. We get back and I put on my trunks to swim, get off the dust and drown any ticks or chiggers that might be hanging on. Esteban and Pelipe join me bathing in their underwear. None of us are naked. The canoe is full of water from the windy afternoon. Cruz has been bailing it out with a big sponge filling it and then squeezing it out. Esteban has been toweling himself dry and puts on his pants over his wet underwear. Pelipe shivering does the same. Mildewed genitals, I think as Esteban picks up a coffee can and starts to help Cruz empty the boat. Pelipe looks and goes to get the tar pot without being told and starts to help bail out the boat. It isn’t work. It’s life.

…

…

DECEMBER 16—

Dusk.

The sun falls into the mountaintop

The clouds grow bright, and then are sucked

into the dark

Read a lot today. Read La Hojarasca. Almost done. Did yoga. Bathed in the lake. Esteban took the day off: I could be nude out on the deck. No boats, no one, no kids. I am happy here now but also I’m ready to leave. Up the mountainside the dry cornfields and the trees all soon will be the blackness before the stars. Soon time to light the candles, boil some potatoes over which I’ll crumble the cheese. Today’s been great. Every day should be like this.

The night is dark. The stars are born

along the mountain’s blackened form.

The night is dark. The stars are born.

Who’s not afraid is not alone.

…

…

DECEMBER 17—

Mr Lizard wants to look

like Mr Rock

so Mr Hawk doesn’t know

that he’s not

and Mr Fly flying by

with a thousand eyes

doesn’t see but to light

and to die

Going to make the bed, in the sheets a rat is dead, squashed by me I guess in my sleep. I guess it was the one I heard gnawing in the thatched roof. The other night it crawled across my face as I slept. What is this? I thought as I woke. A spider? No, it’s a rat. I went right back to sleep, and last night rolled over on it. It probably thought it was safe getting warm next to me. I thought I should save the rat and show it to Esteban saying, If you didn’t kill the snakes there wouldn’t be rats like this climbing in my bed, but I walked out to the back porch and threw it down into the bushes. Needless to say a cleaning took place and an airing of everything.

Esteban’s wife came today with the kids—the youngest boy is two, Basilio, the littlest girl, Francisca, is 4, Domingo’s with them coming down the steps, their mother coming down the steps before them. When she gets to the bottom, she doesn’t tell them to hurry, they take their own time chattering among themselves—I think they’re very smart.

Going back over in the aluminum canoe Mrs Esteban sits upright in the front and does not row. Kids in the middle, Esteban in the back sits and paddles—Domingo sticks out the other paddle and really tries to row with it—I’m sure he thinks he is. Adrian on the rocks the other day said Indians treat their kids like adults from the very first minute.

DECEMBER 18—

A cloudy night, writing by candle light—whippoorwill up in the hills, your usual chorus of crickets and chirring things, down at the beach two fishermen talk around a fire.

I walked from the Santiago dock today over the road that goes to San Lucas and the world beyond, the east side of town. Lots of coffee bushes at the city limits, kind of holly looking, red berries, a lot of garbage, plastic littered through the coffee like it didn’t matter, and a pile of garbage was burning out on the side of the road smoldering filth.

I walked to the Refuge of the Poc, a well-kept park with a little museum, a room of photos of what the people at the refuge are trying to do. They’ve raised to breed a near extinct bird called a Cancho from the eagle family that has a hornlike crest sprouting from its beaky forehead. The eagle lives up on the volcanoes. This bird eats meat but because of no funds they’ve gotten it to eat grain, vegetables and fruit. They were happy about that. They are trying to educate the people that they must plant other trees for the ones that get chopped, that when reeds are taken from their beds, more reeds must be planted. They had been reforesting reeds around the lake, but this year there’s been no money.

Is the poc still here? I ask not wanting to hear.

Yes, the man says, the poc is still here. He showed me its picture: a dark little duck with a pointed sharp bill that is black and has a white ring around it, and there are white rings around its eyes. When they are chicks they are mottled like tigers. They are carnivorous and live off small fish, crabs and larvae in the reeds around.

He shows me a sonogram of the poc’s voice: slashes of white on a black photo: it goes poc poc poc poc, that’s why they call it a poc. Would I like to see one?

We walk to an observatory deck over the reeds and with binoculars he points to a bird in the water far off: a poc. I look through the glasses but as soon as I focus I see a shadowy thing moving into the sunny reeds.

They have two chicks a year and their main enemy, the black bass, lays seventy-one thousand eggs at a time and even if half those eggs don’t make it, that is still a lot of bass.

I tell Francisco—his name’s Francisco—that a lady from Guatemala told me that the black bass had been put into the lake with the best of intentions, to help feed the Indians.

Francisco smiles and says, My mother tells me in the lake there were millions of little fishes everywhere you looked. There were five or six species of fishes, and they were easy to catch, and the Indians loved them, they were very tasty, and when the black bass came, well, like I told you, the black bass lays a lot of eggs and grows to be big, and in two or three years all the little fish vanished and the people said, What happened? Now there’s this big black fish, hard to catch, strong and out in the deep water, and even when they catch it, the Indians don’t like the taste. Black bass will sell for fifteen centavos a pound because nobody wants to eat it. And you open it up: You know what’s in its stomach? Crabs, ducklings, you will even find stones. These fish have very big mouths. Whoever put them in the lake did it for the pleasure of rich fishermen. We still have the lake, the mountains, we still have time to educate, we are going into the schools and telling the children: You can’t throw plastic in the lake. You have to replant reeds. You have to replant trees.

Do you think you’ll save the poc?

Who knows? I think so. We can only hope for funds because we get none from the government.

I looked around the well-kept park whose acres of reeds were sheltering a thousand different living things. Guatemala doesn’t give you anything?

Nothing. One officer in the army gets twenty thousand quetzales a year and what does it serve? This year we are scraping ten quetzales together for gasoline for the boats to plant the reeds. I’ve heard that Germany has cut off aid to Guatemala. I’m glad.

It would be the best thing for Guatemala to help you now and save the environment. I didn’t have to convince him. I ask, The man who worked here who was killed by the soldiers, why did they kill him?

When soldiers see people together doing something they think they are guerrillas. Diego went out that day to collect some data on the poc and never came back. Vanished.

The Catholic priest who was shot in town, what was he doing?

It was the same thing with the priest, he was helping the poor, the widows, but all the soldiers saw was somebody doing something and they thought, Guerrillas. For years we have been saying to the Army, Show us a guerrilla. Bring one down from the mountains and put him in the market. In ten years they haven’t done this. There was once a Colonel coming from Guatemala. The soldiers hid and when the boat passed they shot at him, and the Colonel said, Guerrillas! but it was the soldiers, the fishermen saw them. There are no guerrillas. They shoot the people who think. There was an artist who lived in Santiago, he was becoming world famous: they shot him. We have had enough, the soldiers are going.

Were you at the massacre?

Oh yes.

What happened that night?

Some soldiers got drunk, banged down a man’s door and demanded fifteen thousand quetzales from him. The man said, I don’t have fifteen thousand quetzales. The soldiers said, All right, we’ll take your radio and television. His family ran out to wake up the neighbors, and somebody rang the bells, the word was traveling to meet in the square, there were hundreds of people and the mayor said, Let’s go and talk to the soldiers. This has got to stop. They must let us alone.

I read in the paper that the Minister of Defense, a General Bolaños, said that the work of agitators and the obscurity of night frightened the soldiers into firing.

The moon was out. Otherwise we wouldn’t have gone. It was like daylight and we waved a white flag. There were no agitators, we had no time to talk, they just fired. I hit the ground, I was in the middle of it—Francisco pulls up his pants passed his knees to let me see the white lifted scars: I’m lucky. I hear now there are seventeen dead, some people have vanished and there are more wounded.

…

…

DECEMBER 19—

6:45 AM in the boat docked for Panajachel waiting with numb fingertips surrounded by the early morning fog and the smoke of a thousand cooking fires smelling of sticks and corn stalks—It’s like another world, a dream. Coming across the lake with Esteban we met his children: first Cruz, standing up rowing through the fog, straight at us—Big face, uncut black hair, big eyes all brightness upon meeting—Buenos Días—Then Pelipe and Juan came through the fog. Good morning. Then a fisherman appeared; Esteban and he greet each other in dialect. I say in passing, Buenos Días. An old man standing in his lancha rowing passed us. Good morning.

The boat to Panajachel is beginning to rock, the whistle sounds—Will I be able to write? I don’t want to go to Panajachel to cash traveler’s checks, but I must—The sun not yet quite risen lights up San Pedro’s mountaintop. But all around there’s still the fog. Now the mountain’s illuminated by the sun not yet risen. Now the sun comes down the mountaintop, fog is burned off and everything is real. Well, off to Panajachel. Tomilán Volcano is reflected in the lake scarcely rippled by the oars of fishermen. The sun appears and throws its rays. The lake in a flash is so bright I can hardly see through the burning.

7 PM

Maria barks

Her bark echoes back

To get the last word in she barks again

Her echo returns her last word

It’s funny and then it’s interminable

Same old beautiful night here on the mountainside of San Pedro. Back from Panajachel, most of the Christmas shopping done. Today Panajachel reminded me of New York. Sat with Marion awhile on her porch. She lived in the house out here for seven years and then because of the kids moved back into Panajachel. But she plans on coming back when her little girl’s bigger. She likes the “vibe” here better; she speaks old hippy: when she mentions Santiago, Esteban’s brother, she says he’s on a “natural high”. I say that’s a heck of a lot cheaper and Marion laughs like someone not naturally high who’s smoked a lot of marijuana in her life. In back of the house here and up the hill she’s planted macadamia trees and one day hopes to harvest. She’s disappointed that Esteban doesn’t know how to take care of trees.

I say, He’s so beautiful with the flowers.

But Marion is more concerned about the trees and their pruning. She apologized for the broken pump; she’d been trying to get it fixed. They tell me I am next on the list. Were you inconvenienced?

No. I only use water for the dishes. When I realized Esteban was lugging water all the way to the top of the hill to put in the reservoir, I started to take baths in the lake and I washed my clothes there too. It’s been no problem. I didn’t want Esteban doing all that extra work. When it’s time to water the flowers the kids carry up buckets and tanks strapped to their foreheads and backs. I’m sure they’ll be happy when the pump’s working.

It’s so hard to get things fixed. Esteban knows nothing about pumps, me either. And the lake is sinking so we have to keep moving the pump further out.

Atitlán’s sinking?

Very fast. You know the island across from the house? That didn’t used to be there. And along the shore all those white rocks used to be covered by water.

I tell her that Esteban told me that she’d rented the house to Chuck Norris. What was Chuck Norris like?

Marion laughs and says she never rented the place to Chuck Norris. She said the Indians are incredible liars, it’s part of their culture like barter. You rarely meet an Indian who isn’t a liar, “maybe my maid”—Marion stops to think—”no, even she lies to me now and then.” Marion really laughs at the thought of Chuck Norris.

I tell her Esteban told me Chuck Norris stayed for two months. He saw no one. He exercised and wrote. As long as he was making it up he could have told me it was Charles Bronson.

Marion laughs and I think of Francisco yesterday telling me there still was poc. I tell Marion: I think I saw a poc yesterday at the poc refuge, a caretaker there pointed it out to me with binoculars.

There haven’t been poc in the lake for years. The black bass was put into the lake during the short wonderful reign of Jack Kennedy. They just gobbled up the poc and about a hundred species of tropical fishes.

Then the guy at the poc refuge was lying too?

I’m sure it’s easier to get funds from the World Wildlife Fund if you tell them the poc is living.

But they’re doing such good work.

I’m sure they are.

Well, one good thing, I hear tomorrow the army’s going.

Yes, that’s very good. I’m interested to see what’s going to happen. I was talking to my maid about it. A lot of the problems with the soldiers in Santiago started, well, in Santiago and its environs there are about forty thousand people, and they’re traditionally divided up into districts and there have been rivalries. There have been vendettas. Indians are hot-headed. There is a point they cross and forget it—

But Esteban has been so nice, and so honest—

Look, he lies, you ought to know that. And if Esteban should ever get mad, you just better watch it. Remember they used to be warriors. They fought the Spanish a longtime before they were conquered. I have heard stories of somebody’s dog eating somebody’s chicken and that’s all it takes. I’ve heard of brothers turning in brothers to the soldiers.

You mean they let the soldiers do the dirty work?

Oh yes and it got out of hand and Santiago knows that now that the soldiers are going, they are going to have to watch it. Before the army came ten years ago, Santiago was feuding in all the districts, there was no government, it was a real mess. The army on that level kind of has helped them get it together I hope.

…

…

DECEMBER 20—

I walked through Santiago today along the back road that runs along the inlet of the lake. Walked maybe a mile out of town, it was really Indian, I rarely spoke Spanish, no one knew it. Where are the army barracks? Where did the massacre happen? My communication boiled down to pretending I was shooting a rifle and they’d point in the direction I wanted.

Around the whole compound was a rock fence fortified with barbed wire, not high and very passable. Inside the compound itself were hundreds of coffee trees. There wasn’t a blade of grass anywhere I guess because of the traffic of the soldiers. There really was nothing there. There was no one. The soldiers had gone early in the morning by boat. The massacre happened inside the main gate before what must have been the mess hall and the offices. Corrugated tin sheeting lay in piles, the flimsy wooden buildings were torn apart, the mess hall, the offices, now uprooted poles. There were roofless shower stalls, a cement building half way knocked down. It looked like the wind hit it. Pow!

When I left the compound I found I was being watched by every Indian within sight, all around everyone knew I was there, peering out of doors, standing along the road watching me take a photo of the stone fence and the main gate unguarded now. Word had traveled that I’d come. I got nervous. A man asked me in Spanish, Have the soldiers gone? What a spacey question. Through the opened gate as far as you could see over many acres there was no one all the way down to the lake. Someone had put up a sign near the gate: Neighbors, this town is in our hands.

…

…

DECEMBER 21—

Dusk again, or beyond dusk, night. Walked down to the dock, not a soul but one fisherman not far off. Far off Panajachel lights. A light or two in Santiago. I wave to the fisherman, he waves back. All packed. Tomorrow we row at eleven, get the boat to Panajachel, bus to Guatemala. Hope to be there by five. Finished La Hojarasca (it means The Whirlwind) by Gabriel García Márquez. I really liked it all the way through but at the end I kind of thought, so what? but piece by piece a very powerful book, full of words, young. Finishing Cronica de Una Muerte Anunciada (Chronicle of a Death Announced) also by Márquez, a much later book, simpler words but a more complicated story that he lets flow. A young man is walking off in the morning toward his death, he’s going to get murdered, the whole town knows about it, but for one reason or another nobody does anything. I swung in the hammock, read, looked up at the clouds and mountains, noticed on Tomilán volcano there are brush fires burning. Now that the soldiers are gone the Indians are up there claiming land to plant their corn burning the forests down! Damn, I’m not sure what is worse, soldiers or forests slash-burned.

…

…

DECEMBER 22—

We rowed from the house at eleven-thirty. Juan, Cruz and Pelipe were on the dock to say good-bye. Soon I will be in an airplane, I told them, going to where there’s a lot of snow. As we rowed into Santiago I asked, Esteban, why are there fires up on Tomilán mountain? They are burning the land to plant corn.

I hope they leave some trees for the eagles. Esteban, when you and your boys cut down trees do you ever think of planting other ones?

There are always trees, Esteban says.

I hope so, it’s very beautiful here. Maybe that land you want to sell me, you might want to keep that for your children. What happens if one day they have no land to cut trees or plant corn?

Esteban doesn’t answer and I shut up and row over the lovely shrinking lake. Esteban and I say good-bye wishing each other a Merry Christmas with a handshake. I’ll miss him and his children. I went in to sit at the back of the boat open to the air and lake.

Waiting on the boat sitting next to me were an older American couple, their son and grandson. The chubby grandson had on a t-shirt that says Whale Watcher Hawaii. On the other side of me is an Italian couple, young and not rich, and then a flock of Germans come on followed by a crowd of Indian women and their daughters aggressively trying to sell them things, but the Germans aren’t interested, though the American grandmother is: she asks to look at some wrist bands and suddenly around her and me is a surge of blankets and pot holders in my face. I already have my gifts, I tell them. I want nothing, I tell one particularly aggressive little girl who snarls and spits an Indian curse at me, Wow! and I move to the other side of the Germans and open Chronicle of a Death Announced translating in my head: The day that they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at 5:30 in the morning to wait for the boat in which the bishop was arriving. He dreamed that he was crossing a forest of fig trees in a soft falling drizzle, and for an instant he was happy in the dream, but on waking he felt splashed with bird shit. My Spanish has gotten much better, practice does make perfect, it has strengthened my faith to stick at things. An American man younger than I am, I’d say he was thirty-five, dark hair glasses keeping himself in shape is leaning down talking to his Guatemalan wife who looks Asian and also wears glasses who’s sitting giving a bottle to their daughter in her arms who looks to be about three and too old for a bottle it seems to me with a bruise on her forehead round and blue. She must have really fallen, I do not think abuse. The man is telling his wife in English: I just heard that the United States has cut off military aid to Guatemala. As soon as we get to Panajachel I’m getting a newspaper.

Good, I said butting into his conversation, what they should do now is give the same amount of money to reforest the reeds here and teach more conservation. Two days the army is gone and already the Indians are slash-burning on Tomilán volcano. Soon it’s going to look like San Pedro, no forests at all.

It will do no good, the man said, any money you give to Guatemala never gets spent for what it was intended. This country is full of crooks and the bigger the higher up he is in politics and the biggest crook is the president.

It sounds to me like the United States.

Believe me, it’s worse here. I live here, I know.

He lived here, he knew, but I went on and said, I still think it’s the same in the States. Look at the Savings and Loan scandals, look at HUD.

But people are going to jail there. Here nobody does.

I could have argued that back home the biggest crooks—including the president’s son—were probably not going to jail. But I don’t.

He tells me he has a business installing cable television and now Guatemala wants him to pay taxes equivalent to what he’d pay in the States while he must go on charging his customers Gautemalan rates. He can’t do it. He’ll fold and the cable television will be picked up by the Guatemalan government. He’s being robbed after all his work. They were fighting it out in the courts.

Maybe they feel they’ve been taken advantage of.

Spain started it, the American blurts.

Yes, I thought, and then the Germans came to plant coffee beans and take the land from the Indians and then the Americans came, the United Fruit Company, kicked out the Germans and when Guatemalans wanted Guatemala back—Guatemala had a president who was giving them education and medicine—Guatemala was going to be like the Sweden of the Americas—and this socialist president wanted to get back all the land owned—untaxed—by the United Fruit Company and give it to the Indians; and he was starting to do it too, but in 1954, Allen Dulles, who was the head of the CIA, and also sat on the board of the United Fruit Company, instigated a coup that sent the president into exile and set up a military government that’s been murdering innocent people in the guise of killing Communists ever since paid for by the taxes of American citizens. Spain came first, but it didn’t take The United States long to get to the trough.

When the boat took off, the man came up to me and hanging onto a bar above he leaned forward like an ape and I look up expecting an argument when he says, What the United States should do is come down here and restock the lake with fish and keep restocking it, year after year with some of the species that are now extinct. Trout would do well in this lake, and trout would be easier to catch, it would start the fishing industries up again. But whatever you do in Guatemala you must come and do yourself. Otherwise it won’t get done. Believe me everyone is a crook and no one tells you the truth.

What about the poc? I was at the refuge and I think I saw one with binoculars.

You saw a grebe. Ten years ago I used to go around with the game warden. All over Atitlán there were only two hundred then and every year it got less and less. The poc still lives in other lakes up in the mountains. The Indians here ate the poc: You can’t get it through their heads that when something’s gone that’s it. And the black bass did too; they put that fish in the lake during the thirties, it was an idea of Roosevelt’s.

Liberal good intentions I said and mention the slash-burning fires up on Tomilán volcano: I’m worried they are going to cut all the trees for firewood and not replant any. The caretaker at the house I rented cuts firewood with his children and I asked him what he was going to do when the wood was gone. He told me, there always will be wood. He wanted to sell me land. I told him, Keep it for your children.

He was only thinking of today. He needs that money today. The American looked at the burning mountain and said, They are making their bed and they’re going to have to lie in it. The American sadly shook his head. With the children here between the ages of one and five there is an eighty percent mortality rate. I live in Solala and everyday the little coffins go by. In Solala you can get vasectomies for free, you can get your tubes tied, but nobody does because they’re too macho, and not just the Indians, it’s the Latinos too. They can’t afford to raise two children and they’ll have ten.

I liked him better than I had. I ask him if he thinks that now the soldiers have gone there’ll be a surge of tourism.

Some. Soon in years to come there will be electricity all around the lake. There was no stopping progress.

I mention the massacre and I ask him whether he thinks it was always the soldiers who’d done the killing or if it was vendettas among the Indians.

He says that a guy worked for him who was a drunk and he was always borrowing money from everyone, but instead of paying it back—and sometimes we’re talking fifty cents—he’d go to the soldiers and accuse the guy he owed money to of being a guerrilla—Well, one day, they found him along the road full of holes and it was blamed on the soldiers too but it was the people of Santiago.

A canoe is approaching our boat with an Indian rowing in the front, and an old couple with binoculars in the middle, and in the back is a younger woman—probably the old couple’s daughter, but the daughter and the Indian can’t get the boat to come alongside ours, it was going in circles for a long time. The American started yelling directions at them and then ran with the crew to help the old couple on board, a tall old man, a tall old woman with binoculars around her neck who announces to all of us, We saw the poc! We saw the poc! A whole flock of them. No, you didn’t, says the American, you saw a grebe, the poc is extinct. The old birdwatchers look crestfallen, but then the old woman is undaunted and starts to describe the birds they’d seen. It’s a black water duck, the American tells them: Believe me, I’ve been living here for fifteen years, it’s a grebe.

I walk to the front to watch approaching Panajachel. In the sun in the prow two older men, Americans, are sitting with much younger women in their laps.

Where are you from? someone behind me asks in Spanish.

I look around at a dark older small man. The United States. I’m going home for Christmas.

Jesus is raised from the dead in heaven. There is no baby Jesus. What you celebrate is pagan.

I bet you’re not Catholic.

You’re right, I’m Evangelical.

But you used to be Catholic?

Yes. But I have been Evangelical for ten years, for ten years I am washed in the Holy Spirit.

Don’t you think when families get together at Christmas they are washed with the Holy Spirit?

He didn’t.

Don’t you like to get presents?

Christ is coming. That is my present. The world is going to end. That’s what’s happening in the Middle East, Saddam Hussein is Armageddon. Satan is there right now gathering his followers.

I tell him: So many Christians run around doing the work of Satan, Satan doesn’t have to do anything, he can just sit back, relax and let the Christians do all the dirty work. Satan’s hands are clean.

The old man licks his lips warming up to an argument which he is looking forward to having because I’m going to hell and he isn’t.

But I’m leaving. Merry Christmas I smile at him.

Back at the poop I open my book and overhear the American talking to the old couple telling them if they are going to retire right now on Lake Atitlán is a good time to buy, the prices are good, but in a short time, ten years or a little more, there’ll be no more land for sale. You can live down here like a king on your pension. The tall old man leans toward the younger darker one and listens.

Just before we dock the American wishes me Merry Christmas and says how much he misses the Jewish delis on the Lower East Side. Had I ever been to Katz’s?

I mention the wonderful hot dogs there and he reminisces. I wish him luck in court and I’m off lugging my bags through Panajachel. I get to the bus right before it takes off. The bus is packed and I slip through toward the back and sit down on a seat where two men are already sitting: We are snug and there are more getting on, but the bus thinned out at Solala; after that it was fine. It took the same amount of time as the cab and it cost eight quetzales.

At the Posada Real Hotel the water was running, in fact, I had a hot shower. That was a surprise. I had the room you had before, number 11. I had dinner at La Altuna. Three martinis; shrimp ceviche and Paella, the house dish of rice, shrimp, mussels, chicken and fish—delicious. I’d picked up the newspaper, La Prensa Libre, whose headline reads: UNITED STATES CUTS MILITARY AID BECAUSE OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS. The story however is all the way back on page 37, several paragraphs. Richard Boucher, speaking for the State Department, says, We are cutting off the aid because the government of Guatemala has promised to punish the offenders but no offenders have been brought forth to be tried. Though President Vinicio Cerezo wishes otherwise the massacre of Santiago Atitlán cannot be ignored. Good, I thought, and paged through the paper coming upon this story:

NEW TRAGEDY IN SANTIAGO ATITLAN

A country couple riddled with bullets.

A pair of country people were killed by gunfire when a group of armed men entered the house of Carlos Bracamonte, 14 kilometers outside of Santiago Atitlan in Solala along the Tomilán San Lucas.

According to official data the couple was killed last night by 5.56 caliber arms. The victims are José Pompoy Mendoza, 64 years old, and Juana Coché Tacaxaj, 52

Both were caretakers of Bracamonte’s house when the attack happened. The man received 5 fatal wounds, the woman 3.

Before would this have been blamed on the soldiers?

I walked to the main plaza. The National Palace is lit up with twinkling Christmas lights. It’s so ponderously big and the lights are so far away and small the effect on the Palacio is ridiculous, ineffectual. The big Christmas tree in the center of the plaza has big bows and electric candles; in front of it a rock concert is taking place on a stage. I look up at the night; in the polluted sky two stars barely shine. I look at the big crowd. The steps of the National Palace are full, here and there machine guns with young soldiers appear. The Japanese Red Cross has set up a hospital tent in anticipation of what? a riot? a massacre? bad acid trips? The rock concert in progress has a feeling of great innocence and a yearning to be something it isn’t, I mean really this is Guatemala: these kids should be playing marimbas. Kids up front jump up and down like what they’ve seen on television. Indians and older folks on the outskirts watch a few boys with their shirts off thrown about above the crowd, but mostly the crowd stands and looks and does not move, partly because so far the music isn’t that good, and partly I feel to move isn’t macho, the only people around me moving at all are women, tourists and homosexuals. The bands are not original though one band called Psycho seems to have made rock and roll their own, older guys, our age, who end their set with Led Zeppelin’s Moby Dick. The last band was American. I’d been impressed how quickly one band had followed another. Till the American band came on. Now everything was, Check, Check, testing 1, 2, 3. The crowd got restless but full of humor and started yelling, Check! Check! Someone yells, Fuck you! but they’re in a good mood. The band’s name is Halo: “We are Christian Rock and Roll,” the generic blond long haired lead singer announces in English: “We can’t speak Spanish.” He says, as their set starts with an orchestrated tape: “In the beginning in the Garden of Eden Adam lived with Eve and then the Serpent came,” but no one knows a word he’s saying and when the band starts playing, it has a steady loud beat. “Turn it up! Turn it up!” the singer screams and a lot of people start to dance.

hola Don Yorty,

my name is Xelani Luz and I live in Santiago Atitlan. your story was very moving to me as it talks of an event that was fundamental for our town. this has since passed into history and there are very few photographs of that event and the social reaction within the town in the weeks afterward.

I have been encouraged to ask you about the possibility of getting some better resolution copies of your images to include in an educational project that I am part of called the Archivo Digital Etnografico Atitlan. I am also good friends with Santiago and his daughter Josefa and am well acquainted with Patziapa, too! I would also be very willing to make sure some of these wonderful pictures get to them. my email is archivoatitlan@gmail.com.

thank you for sharing!

Xelani Luz