© 2021 Don Yorty. All rights reserved.

© 2021 Don Yorty. All rights reserved.

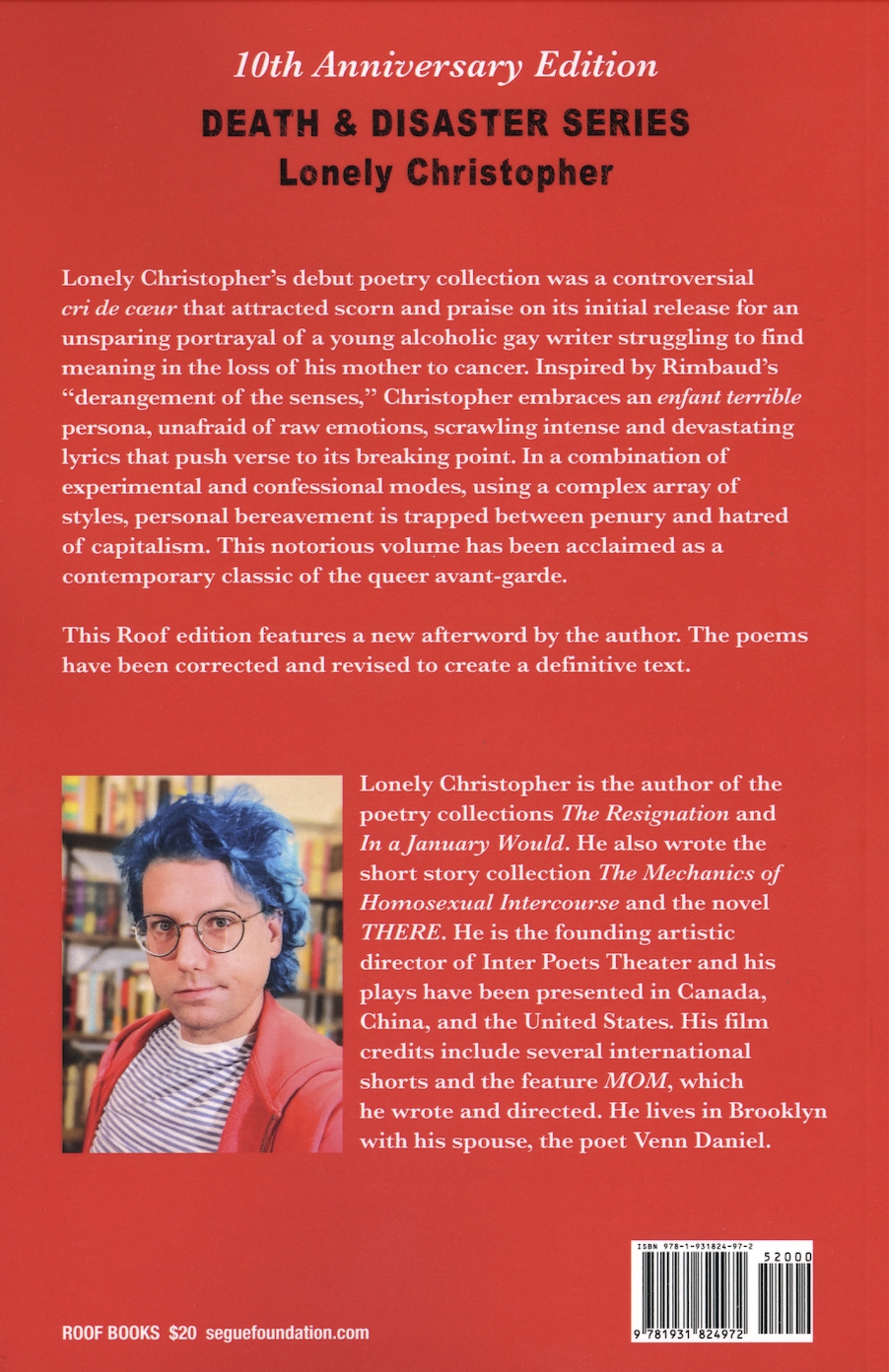

Death & Disaster Series was written by Lonely Christopher during his early twenties when his mother was dying and shortly after she died, writing poems instead of committing suicide. I too had a hard time surviving my twenties so I can relate. I knew what I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how to do it, lacking the experience that only time gives. I knew that I needed to write although my parents and family were telling me to get a job. It was a tough row to hoe, and as I read Death & Disaster Series, I knew that Lonely Christopher had hoed it too.

He toils even today with the capacity to read many books, see many movies and write essays about them. During his terrible twenties when he wrote his indulgent Death & Disaster Series, he also wrote a screenplay with the wherewithal to gather funds to pay good actors, hire a director and produce a movie I really admire called Mom. Watch it.

Good poems are worth rereading so it makes sense to have Death & Disaster Series reprinted for a generation that hasn’t read it yet.

The book’s in three parts, the first is “June,” a short month, but the cup runneth over here; there are thirty-five poems, many of them short, in the moment, letting what comes come, off the cuff

The hospital blanket

chaffing the throat

that cracks a family

open like candy.

Or describing indescribable joy:

There’s a blue tinge of joy

in the air here’s why it’s there

to ask questions. Why

does my spine

quiver at the sound of a violin

bow caressing a string.

How do good things happen.

Why does the dominion

haunt the waking

writing in the pencil

as joy’s writ on the air

when you breathe

it disappears.

“Crush Dream,” the second part, puts words where they belong and with just the right sound. And the sound of words abound. Here there are adventures going on. In “No,” nouns become verbs. The poet dinosaurs blank space and Decembers indolence. I had a lot of fun.

The third part, “Challenger,” is full of disasters the poet survives although he tells us that he dies, but just like his reprinted poems, again he’s born. With love.

Idumea

Everything is red. The ground is red,

The blood. For some

of us there is a future, though I’ve had

my doubts. For some

of us are haunted by loves beyond love.

We walked through the mall or I never

met you. There is a lens marked terror

and when I look through it,

all I can see is my own failure.

Fleeting as it is, it cannot stand, not

against you, virtuous and muddled motherhood,

delighting in a clear day and raked through

by circumstance, left standing, out of force,

getting old, having it all taken out of you,

surgically, piece by piece, till science

steals away your body, till I can’t look

at your picture for the pain.

And I can’t remember your voice.

Everybody gets burned down to the ashes

of everlasting love. Am I born to die?

Yes—but why?

Be quiet now, but sear a coal-strong fury

through everything within me, every day.

There’s nothing left and no reason but to

Carry the world inside you.

What will become of me?

Might I take the voice and the strength

That you left and see the flaming skies.

There is the despair of the heart

And the horror of the spectacle

But they are by no means the same thing.

………………..This is America

………………..or,

………………..I love you, Susan.

I went over to Brooklyn to record Lonely Christopher. He shares his apartment with his partner, Venn Daniel, and Lucy, his pit bull, who loved me a lot and laid by the tripod to knock it with her tail in her slumber, but only in moments of silence so that I could edit out the sudden tremors the gentle Lucy caused. You have to walk blocks to get there, but it’s worth it, on the corner of a park. Lonely was ready to page through the book reading by chance what came along. He doesn’t make one flub because he knows what he is doing. It’s all in the Vimeo below. Enjoy.

Death and Disaster Series is published by Roof Books. You can check it out here:

This new edition ends with an “Afterword,” which I’d like to include. Here it is:

“If you kill yourself, I’ll come back from the grave and haunt you!” said my mother. This conversation occurred during my penultimate visit, after she learned there was no hope but before she became permanently bedridden. I accompanied her on a final mall walk. She adjusted her wig and told me she always admired me for standing up to my bullying, emotionally abusive father. She was starting to tie up loose ends, sharing long suppressed family secrets about my adoption: that I had several half-siblings I didn’t know about, although the girls had died as infants in a trailer fire, and she denied remembering the name of my biological mother (I think she was lying).

Her concern over my wellbeing was warranted, as I’d suffered suicide attempts before and after my recent undergraduate experience and was currently being helplessly subsumed by depression and alcoholism. The next time I saw her, this worry had calcified into inarticulate bitterness. She hadn’t the strength to lift her head, but she focused on me from across the living room, and hazily slurred, “What are you going to do?” She could no longer converse, shed of wit, frightened about what was happening, muffled by sedatives, her remaining disapprobation was agonizing. What was I going to do, without her—fall into the abyss over which I teetered?

As my own condition deteriorated, I did what I could to hide the sordid details. I didn’t want my parents to know that I smoked under-the-counter menthol cigarettes or started to drink 40s of Ballantine immediately upon waking in the afternoon. The cover story was that my burgeoning writing career would imminently turn financially viable. Until then, I was unemployed and dependent on my mother to pay my rent. In retrospect, that arrangement lasted only about a year, which wasn’t as desperate as it felt at the time. I lived in fear over the withdrawal of parental grace and my identity bifurcated into an authentic self and the weak guise I presented them. I had only come out to my mother the year prior, certain that my sexuality would further disrupt an already tenuous relationship to my family. (It did.)

I was a young and reckless city boy running headlong into the consequences. My parents were folksy protestants living in the same culturally bankrupt corner of the state where they’d been raised. My mother became frustrated with my obstinacy, wondering why I couldn’t just get a job at McDonald’s, and accusing me of acting like a spoiled “debutante.” Unmoored after college, I had no ambitions other than being a writer, while most of my friends left the area to continue their education or start their adult lives elsewhere.

My mother was diagnosed with stage four ovarian cancer, a delayed detection that I suspect was related to sexist malpractice, her doctor ignoring complaints until it was too late. She kept the severity of her illness from me for as long as possible, not merely to protect her children, but because she did not endorse her terminality. It wasn’t difficult to keep me in the dark since I was tremendously self-absorbed. But she couldn’t deny the treatments were escalating. First, she lost her hair and then they started removing organs, her uterus and intestines. She was coughing and vomiting blood, constantly nauseated.

She insisted that she was going to beat it. Even when the medical establishment released her to palliative care, she began seeking increasingly desperate and disreputable alternative treatments. She was quietly furious when her husband gave her a pamphlet of gravestones, asking her to pick what she wanted. My father mistreated me but was an attentive aide to his spouse during her last year. He’d lost his fortune in the recession, was now losing his wife, and was briefly humbled.

I spoke to my mother at least weekly on the phone, her voice growing thinner with each call. She started taking painkillers that made her hazy. One day I checked in and my father picked up. I asked to speak to her, but his reply was, “She doesn’t talk anymore.” I was confused because we’d just conversed a few days before. I asked my father what that meant. “It means you have to come home.” I asked when. “The next flight,” he said.

A grade school friend picked me up at the airport. I found my mother in the living room, where her hospice deathbed had been installed. She was skeletal, could barely move. When she saw me, she said, “It’s amazing. It’s amazing.” Her pastor interpreted those words to mean that she had pierced the veil and was getting a sneak peek at heaven. I thought, What the fuck are you talking about, you crazy asshole? She was saying it was amazing that her son had materialized out nowhere to be with her in the final days.

This book was an urgent text because I had nowhere else to put my feelings during an unprecedented crisis. I had no other way to respond to my mother’s destruction than in poetry, the occluded realm of revelatory debasement where I frequently bastioned myself with the assistance of bottle after bottle of cheap beer. I scrawled without restraint. That’s what makes it a wild and immature book, both qualities that I heralded as assets rather than failings. I hated the capitalistic society that contributed to the emotional constipation of my family and the injustice of my mother’s illness, so I endeavored to live in calamitous defiance of that system and create work that was an extension of my opposition. That meant being messy, ugly, unfiltered, radically honest.

Stylistically, I attempted to wed the aesthetics of linguistic experimentation with outrageous confessionalism. It was difficult for me to directly address my subject, so I often had to examine the detritus twisting around the problem to determine the shape of the undefinable problem itself. The stream of conscious is fractured and polluted, cohering briefly in malformed lyrics seething with frustration and resentment. Fuck clarity—it never did anything for me. I embraced the unspeakable, expressing my own emotional disjointedness through fragmented references and semantic convolution.

There are no commas in Poems in June, to preserve a tumbling sense of prosodic flow, while each period becomes a defiant stomp. The lack of punctuation creates a destabilizing exigency, as these poems attempt to hold space for the base and artless rage and confusion I felt when confronted with irrepressible emergency. The tension in these tough, almost bloody shreds of verse originates in excessive necessity.

Crush Dream was undertaken after a period of inarticulate mourning, when my mother died, and I could not write anything for months. It begins to evince some distance from panic, making room for formal maneuvering, baroque postures, and irony. It doubles down on previously established themes, introducing new approaches, trying to apply a buoyant pop vocabulary to grim fixations. This duality is present in the title, which contains both positive and negative meanings: the object of my affection or the demise of my potential.

A claustrophobic June opens up geographically to encompass some far-flung locales. Whereas the previous section was largely confined to a single room, declaring “No California,” the poems now venture to places like San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Baton Rouge. Grammar begins to normalize and lines lengthen into more realized sentences. The scope widens in the search for answers.

Irresolution becomes the dominant mode of Challenger, which learns the hard way that the accumulation of grief is often an inextricable wound. The drive for meaning is what motivated me, yet I didn’t recognize as a deficit the stubborn and conceited notion that I could write my way out of trouble. The opening poem, “Something Happened,” was an attempt to as directly as possible provide witness to trauma.

Such intensity of focus wasn’t sustained, as I ventured afield to address new and various subjects, only tangentially related to the facts of my mother’s illness, but still reconnecting with my primary goals, reinscribing my failures and frustrations along the way. Except in scattered provocations, the language here bends toward the prosaic and comprehensible, emphasizing conventional sentence structure, even going so far as to consistently employ commas before line breaks, where you’d expect them.

The use of religious tropes and symbolism in this series relates to my family’s perfunctory sense of Methodism, which never engaged me seriously, although I was compulsorily involved as a minor. My mother was a more enthusiastic participant in religious belief but with her it was almost a welcome yet incidental byproduct of the sense of community to which she was gregariously drawn. My father transformed from a disinterested fair-weather churchgoer to brainwashed neoconservative self-righteous fanatic in later years.

Writing as an atheist, I was motivated to subvert and expose the prejudices and hypocrisies of Christianity, although I allowed myself to take some solace in elegiac traditions like the melancholy choral music of the sacred harp songbook, which uses simple notation to pose deep, unanswerable queries about existence. But if there was any blood cult in which I placed my faith with the furor of the convert, it was poetry.

At the time, I viewed my constant drunkenness and promiscuous sexual encounters as liberatory practices, although now it seems to me as self-medicating. The hookups I believe were less destructive in nature. When this book was first published, some moralistic readers painted me as a feckless and offensive slut. Revisiting the work, I find it rather tame in that regard. My sex life was disorganized and rarely sober, but it was a way of connecting with other people and affirming the validity of my queerness. Admittedly, I had low self-esteem and body dysmorphia, but I can still appreciate the exploratory nature of my desire (and my poetry).

The three movements in this series represent different stages in my grieving process. I started writing during the end of my mother’s life, while being ravaged by the enormity of the situation. I arrested myself in a stifling garret (I exaggerate—it was really a two-bedroom unit on the top floor of a Bed-Stuy apartment complex) with little else for sustenance but cigarettes, alcohol, sandwich meat, and books. My roommate had left for the summer, abandoning me to a humid and hostile environment, the hottest June of my life.

I was being crushed by June. The sense of immediacy seemed to resonate with people, the pounding repetition, each “June” a fist to the skull. The pastoral as hellscape, the family as existential crisis, the economy as antagonist. Unfortunately, yet inevitably, I think I was chasing after the impossible. I wanted my art to imbue this experience of loss with profound meaning and to literally synthesize a redemptive settlement of my anguish. Despite attempting catharsis, the project felt unfinished. I had to keep working. Yet the longer I searched for absolution, the more bathetic my efforts became.

I learned that grief can be isolating and narcissistic. What I created was far from the commemoration of a beloved mother, rather a tangle of humiliation and defeat swirling around her disappearance. There was no solution. I could manipulate language to express the agony, to trouble the narrative, to expose the wound, but it wasn’t going to fix the problem. I was only on the precipice of catastrophe. My mother’s death was the instigating incident leading to further conflict and degradation. I was only beginning my downward spiral into dissipation, desperation, and eventual homelessness from which I’ve been slowly recovering over the years through sobriety and mental health treatment.

After the coroner removed her body from the house, my father threw a box at me. It contained all my books and press clippings, which my mother had carefully collected. It was a record of my successes, and my father wanted it gone immediately. He told me the name of my birth mother and gave me a picture of her that I’ve since lost. In an act of mourning, I shaved my head; he became infuriated that I left some hair around the sink. My mother donated her body to science so there was no funeral. My father’s refusal to schedule a timely memorial was another way for him to stay in control, for things to happen on his terms.

A huge storm delayed my return to the city. Eventually, my father drove me to the airport. He said, “When you were born, I made an oath that I’d never forsake you.” Spoiler alert: he quickly forsook me. We don’t talk anymore. With my mother gone, there was no barrier to quell his abuse. It worsened. I learned how to stand up for myself, but it necessitated complete separation. Her death signaled the end of our family.

Losing my mother at an incredibly vulnerable juncture in my post-adolescence damaged me in a wide variety of ways it took a long time to begin to recognize and cope with. I also explored my sense of abandonment and uncertainty in the film MOM, which I wrote and directed around this time. Without the faculties or resources to seek medical and psychological help, and considering the inimical influence of my remaining parent, creative writing was not the best possible or most restorative outlet for these struggles, but it was the only one available. I don’t regret placing my faith in art, though questions remain regarding the efficacy of that approach.

This text, begun a decade ago, is meant to be audaciously embarrassing, a flagellation, a confrontation. I still accept it on those terms. It is indeed a “young” book that’s unapologetic about its impetuous rawness. I present it now with a fresh edit not intended to mask ungainliness but refine and clarify my intentions. Its inherent structure and attendant strengths and weaknesses remain intact, along with the number and sequence of the poems themselves. Using all the methods at my disposal, I screamed my injuries into verse, propelling lofty motives into the stratosphere like a space shuttle, only to watch in horror as the machine careened back down to earth and crashed into the ocean.

—Lonely Christopher

Brooklyn, June 2021